| x | x | ||||

|

|||||

| x | BACTERIOLOGY | IMMUNOLOGY | MYCOLOGY | PARASITOLOGY | VIROLOGY |

| From CDC web site: May 16, 2005 | One Traveler’s Ordeal with Severe Malaria: A Cautionary Tale |

||||

| Stuart Ver Wys’ fever started four days

after his ship left Port-au-Prince, Haiti, and two days before it was to

arrive back in Lake Charles, Louisiana.* In addition to his fever, Mr.

Ver Wys, an otherwise healthy 60-year-old man, had no appetite for

either food or water. What had begun as a good and meaningful trip

seemed to be ending badly. |

|||||

In downtown Port-au-Prince, May 2005. (CDC photo) |

In HaitiMr. Ver Wys was returning home after spending three weeks in Haiti working for Friend Ships, a humanitarian group based at Port Mercy in Lake Charles. He had left for Haiti on January 15, 2005, aboard the Spirit of Grace, one of Friend Ships’ fleet of ships it uses to carry out its mission. He had worked in Haiti’s capital, Port-au-Prince, delivering the relief material the ship carried to its intended recipients. He enjoyed this work and found it very rewarding, as he had enjoyed all his previous work with Friend Ships during the past 8 years. And during this, his first trip to Haiti, he had come to love the Haitian people and their country, so vibrant and full of hope in spite of the many problems they face. During his first week in Haiti, Mr.

Ver Wys slept on the ship. He then moved on land and spent the rest of

his stay in Port-au-Prince, sleeping in a medium-sized tent on the

outskirts of the city. There were many

mosquitoes and other bothersome insects, especially at night, and

Mr. Ver Wys occasionally used insect repellents to keep from getting

bitten or stung. However, he did not use a bednet, even though his

sleeping quarters were neither air-conditioned nor screened against

insects. A bednet, providing a protective enclosure around the sleeper,

would have shielded Mr. Ver Wys from mosquito bites at night. |

||||

About Malaria PillsUsually,

when people travel to parts of the world where there is a malaria risk,

their doctors prescribe them medicine to help prevent malaria. Mr. Ver

Wys did not take any malaria pills, even though the ship’s doctor had

recommended that he take chloroquine tablets to keep from getting

malaria. Mr. Ver Wys thought that his risk for getting malaria was low,

and he was concerned about unpleasant side effects that the malaria

pills could cause. Several other crew members did not take their

medicine as directed or follow other prevention guidelines, either.

Besides, during other trips working with Friend Ships on the island of

Roatan in Honduras and in Guatemala, Mr. Ver Wys had not taken malaria

pills. Since he did not get malaria on those trips, he thought he did

not need to take anti-malaria pills on this trip either. |

|||||

Illness in Lake CharlesMr. Ver Wys still had a fever and loss of appetite when the ship docked in Lake Charles on February 19. Shortly after his return, since he still was not getting well, he went to the emergency room of a local hospital to find out what was wrong with him. There, he was misdiagnosed as having the flu. The hospital treated him with intravenous fluids to relieve his dehydration and sent him home the same day. During the next few days, his symptoms got worse, and he became weaker and confused. Mr. Ver Wys no longer remembers anything from the later time when he was sick. Friends, relatives, and health workers who cared for him during his illness have had to tell him the rest of his story. Mr. Ver Wys passed out several times in the days after his trip to the emergency room, and a visiting Friend Ships doctor decided he needed to go to a hospital immediately. Mr. Ver Wys went to the W. O. Moss Regional Medical Center, a Louisiana State University hospital in Lake Charles, late at night on February 24. At the hospital, his speech was slurred, he was slow to respond to simple commands and had an abnormal nerve response (called “ankle clonus”) on his right ankle. Then he became increasingly confused. These symptoms indicated that his brain was not functioning well. He had a high fever at 103 degrees Fahrenheit, his blood pressure was alarmingly low, and both his pulse and his breathing rates were abnormally high. His laboratory tests showed that he had lost blood, and that his platelets (a blood component essential to blood clotting) were low, putting him at risk of severe bleeding. The lab tests suggested that his liver and kidneys were also not functioning well. His sister Mary Lou and his brother George, who both traveled from Michigan to Mr. Ver Wys’ bedside, were distressed by his appearance and were afraid that he would die. They discussed what arrangements for long-term care should be made if he were to survive but have brain damage. Mr. Ver Wys’ friends at Friend Ships put a message on their Web site asking people to pray for his health. |

|||||

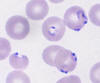

Blood smears from Stuart Ver Wys, showing red blood cells infected by Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites. (Courtesy of LSU HCSD - W.O. Moss Regional Medical Center) |

Luckily for Mr. Ver Wys, two of the physicians who

saw him at the hospital were, respectively, from Pakistan and Peru,

countries where malaria frequently occurs. Once they were told Mr. Ver

Wys’ travel history, they put malaria high on their list of potential

diagnoses. They suspected that during his stay in Port-au-Prince, Mr.

Ver Wys had been bitten by a mosquito carrying malaria parasites. The

parasites entered Mr. Ver Wys’ blood, where they

grew and multiplied freely because he had not

taken any antimalarial drugs.

The hospital’s laboratorians promptly

took blood samples from Mr. Ver Wys and spread the blood on a microscope

slide (“blood smears”). They examined the blood smears under a

microscope and saw malaria parasites of the type called

Plasmodium falciparum. Malaria caused by this type of

parasite is very serious and can kill people who get sick from it. The

parasite count in Mr. Ver Wys’ blood was high: on the blood smears, one

out of every 20 red blood cells was infected by a malaria parasite.

These test results explained Mr. Ver Wys’

symptoms. His malaria was affecting his brain (cerebral malaria),

which is one of the most deadly effects malaria can have on the body.

|

||||

Stuart Ver Wys (center) visiting the Intensive Care Unit where he was treated, and two of his physicians, Dr. Mohamed Sarwar (left) and Dr. Carlos M. Choucino (right). (Courtesy of LSU HCSD - W.O. Moss Regional Medical Center) |

TreatmentOnce Mr. Ver Wys was diagnosed with malaria, his case was treated as a medical emergency. He received two powerful antimalarial drugs, quinidine (similar to quinine) through a constant intravenous drip for rapid delivery, and doxycycline, an antibiotic that also kills malaria parasites. In addition, he also received multiple transfusions of blood cells and platelets to correct the damage done to his blood by the malaria parasites. Because W. O. Moss Regional Medical Center, like most hospitals in the United States, treats malaria only rarely, his doctors also consulted CDC on the telephone** and used CDC’s Web-based Guidelines for Clinicians for the treatment of this difficult case. For several days Mr. Ver Wys’ body struggled against malaria. He moved between different levels of consciousness. Finally, after four days in the Intensive Care Unit, Mr. Ver Wys began getting better, eventually regaining normal consciousness and normal vital signs. He was discharged after 10 days in the

hospital. The total cost for his hospitalization was $23,383.15. |

||||

Stuart Ver Wys convalescing. In the background is the Spirit of Grace, the ship that took him to Haiti. (Courtesy of Clark Davis) |

ResolutionAt the time of this interview, two weeks after his ordeal, Mr. Ver Wys is back on his ship. He has begun to work again. Even though he feels well, he has not yet recovered his full strength and still needs to gain back the weight he lost while he was sick. “Next time I travel to a malaria risk area, I will take my pills," Mr. Ver Wys says. "I hope that my story will convince other people to do the same."

|

||||

Keep Yourself Safe from Malaria

Footnotes* Stuart Ver Wys gave the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention permission to interview him, discuss his medical history with his attending physicians, and publish his story. ** Health care providers needing assistance with diagnosis or management of suspected cases of malaria should call the CDC Malaria Hotline: 770-488-7788 (M-F, 8am-4:30pm, eastern time). Emergency consultation after hours, call: 770-488-7100 and request to speak with a CDC Malaria Branch clinician.

|

|||||

|

|

|||||