| x | x | |||||

|

||||||

| BACTERIOLOGY | IMMUNOLOGY | MYCOLOGY | PARASITOLOGY | VIROLOGY | ||

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Let us know what you think |

||||||

|

TEST YOUR KNOWLEDGE |

||||||

|

Introduction Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) have been described as “hidden epidemics,” comprising 5 of the top 10 most frequently reported diseases in the United States. An estimated 12 million new cases of STDs occur each year in the U.S., which has the highest rate among all developed countries. In the developing world, STDs are an even greater public health problem as the second leading cause of healthy life lost among women between 15 and 44 years of age. The STD epidemic in the developing world, where atypical presentations, drug resistant organisms, and co-infections (especially with HIV) are common, can have a potentially larger impact on our population due to increased international travel and migration. The health consequences of STDs occur primarily in women, children and adolescents especially among racial/ethnic minority groups. In the U.S., more than a million women are estimated to experience an episode of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) per year. The number of ectopic pregnancies has been estimated as 1 in 50, and approximately 15% of infertile American women are thought to have tubal inflammation as a result of PID. Adverse outcomes of pregnancy due to untreated STDs include neonatal ophthalmia, neonatal pneumonia, physical and mental developmental disabilities, and fetal death from congenital syphilis. Among all age groups, adolescents (10- to 19-year-olds) are at greatest risk for STDs, because of a greater biologic susceptibility to infection and a greater likelihood of having multiple sexual partners and unprotected sexual encounters. Minority groups such as African-Americans and Hispanic Americans have the highest rates of STDs. STDs and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections share common risk factors for transmission. Genital ulcer disease increases the risk of HIV acquisition and transmission by 2- to 5-fold; urethritis and cervicitis increase the risk by 5-fold. Treatment and control of STDs at the population level may result in decreases in HIV incidence among populations with high rates of STDs. STD control should be considered an important component of HIV prevention in public health as well as clinical practice. Effective clinical management of STDs should include screening of sexually active individuals with appropriate laboratory tests, providing definitive diagnosis and treatment, client-centered risk reduction and education, and evaluation and treatment of partners. Screening of asymptomatic patients is of utmost importance in order to prevent sequelae. Screening for STDs among sexually active women, especially pregnant women, is essential since roughly 70% of chlamydial infections and 50% of gonococcal infections are asymptomatic in this population. Unfortunately, the barriers to effective STD prevention are multiple, including the biological characteristics of STDs, lack of public awareness regarding STDs, inadequate training of health professionals, and sociocultural norms related to sexuality that can lead to misperception of recognized risk and consequences. |

|||||

Figure 1

Figure 1Reported cases of syphilis by stage of infection: United States, 1941–2006 CDC

|

Genital Ulcer Diseases: Overview A genital ulcer is defined as a breach in the skin or mucosa of the genitalia. Genital ulcers may be single or multiple and may be associated with inguinal or femoral lymphadenopathy. Sexually transmitted pathogens that manifest as genital ulcers are Herpes simplex virus (HSV), Treponema pallidum, Haemophilus ducreyi, L-serovars of Chlamydia trachomatis and Calymmatobacterium granulomatis. Genital ulcer diseases facilitate enhanced HIV transmission among sexual partners. In the presence of genital ulcers, there is a 5-fold increase in susceptibility to HIV. In addition, HIV infected individuals with genital ulcer disease may transmit HIV to their sexual partners more efficiently. HSV is the most common cause of genital ulcers in the US among young sexually active persons. T. pallidum is the next most common cause of GUD, and should be considered in most situations despite the decline in cases of syphilis nationwide (figure 1). Chancroid, caused by H. ducreyi has infrequently been associated with cases of GUD in the US, but has been isolated in up to 10% of genital ulcers diagnosed from STD clinics in Memphis and Chicago. Chancroid is the most common genital ulcer disease in many developing countries. Lymphogranuloma venereum or LGV caused by L-serovars of C. trachomatis and granuloma inguinale (donovonosis) caused by Calymmatobacterium granulomatis are endemic in tropical countries and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of genital ulcers from a native in the tropics or in travelers. The prevalence of pathogens that cause GUD varies according to the geographic area and the patient population. A single patient can have genital ulcers caused by more than one pathogen. Despite laboratory testing, approximately 25% of genital ulcers will have no identifiable cause. There is considerable overlap in the clinical presentation of herpes, primary syphilis and chancroid, the three most common causes of genital ulcers in the U.S. Inguinal lymphadenopathy is present in about 50% of the patients with genital ulcer diseases. Genital herpes typically presents with multiple, shallow ulcers and bilateral lymphadenopathy. Primary syphilis can usually be differentiated from genital herpes by the presence of a single deep, defined ulcer with induration. A distinction may be made between syphilis and chancroid, which commonly presents with a painful, undermined ulcer with a purulent base and tender lymphadenopathy unlike syphilis. The cause of genital ulcers cannot be based on clinical findings alone. Diagnosis based on the classic presentation is only 30% to 34% sensitive but 94% to 98% specific. Therefore, diagnostic testing should be performed when possible. Serologic testing for syphilis should be considered even when lesions appear atypical. If available, darkfield examination or direct immunofluorescence on the lesion material should be performed as the definitive tests for T. pallidum. Genital herpes can be diagnosed in the presence of typical lesions and/or positive serology, but herpes culture should be performed when the diagnosis is uncertain. |

|||||

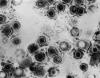

Figure 2

Figure 2Transmission electron micrograph of herpes simplex virus CDC/Dr. Erskine Palmer

|

Genital Herpes Simplex Genital herpes simplex virus infection affects up to 60 million people in the U.S. and can be caused by both herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and type 2 (HSV-2) (figure 2). The seroprevalence of HSV-2 has increased over the past three decades to 22% among individuals 15 to 74 years of age (figure 3). Behavioral factors correlated with seroprevalence include cocaine use, multiple sexual partners and early sexual activity. Most patients (40%) infected with genital HSV-2 and two-thirds of the patients infected with HSV-1 are asymptomatic. Hence genital herpes is often acquired from individuals who have never been clinically diagnosed with herpes. Transmission of HSV between sexual partners has been estimated at 12% per year but can be as high as 30% among women who are partners of infected men. Women have a 5% to 10% higher seroprevalence of HSV-2 than men, suggesting the increased risk of acquisition. Genital lesions acquired through sexual contact are typically caused by HSV-2 (figure 4-6), while oropharyngeal lesions acquired through non-genital personal contact are most commonly due to HSV-1. However, both viruses can cause genital and oral infections. HSV-2 causes the vast majority of genital herpes in the U.S., but HSV-1 accounts for 5% to 30% of first-episode cases. After mucosal or cutaneous contact, HSV replicates in the dermis and epidermis and ascends through the sensory nerve fibers to the dorsal root ganglia. Once established in the sensory ganglia, the virus remains latent for life with periodic reactivation and spreads through the peripheral sensory nerves to the mucocutaneous sites. Most patients seropositive for HSV-2 have subclinical, undiagnosed genital herpes. About one fourth of the patients with first episode of genital herpes have positive HSV-2 serology suggesting prior asymptomatic infection. Thus, the first clinical episode of genital herpes could reflect either primary infection or a first recognized episode of a past infection. Primary infection with HSV-2 is characterized by a prodrome of systemic symptoms including fever, chills, headache and malaise. Pain and paresthesias around the outbreak site precede the appearance of lesions by 12 to 48 hours. The hallmark of genital herpes consists of grouped vesicles or pustules that lead to shallow ulcers. Atypical lesions of genital herpes include linear fissures of the vulva, cervical ulcerations, vaginal discharge, papules and crusts. Patients may have accompanying tender inguinal lymphadenopathy. Urethritis, rectal or perianal symptoms may be present if there is urethral or rectal involvement. Immunocompromised patients may present with extensive perianal and rectal manifestations. Extragenital manifestations of HSV include ulcerative lesions of the buttock, groin, thighs, pharyngitis, aseptic meningitis, transverse myelitis and sacral radiculopathy. Primary infection with HSV-1 is manifested by genital ulcers in about one-third of patients. Another one-third may present with orolabial lesions or pharyngitis and the remaining patients are asymptomatic. The genital lesions caused by HSV-1 are indistinguishable from those of HSV-2. Recurrent genital herpes is usually a milder syndrome than primary infection. The recurrence rate of genital herpes due to HSV-2 is much more frequent than due to HSV-1. Similarly, the recurrence rate of orolabial infection due to HSV-1 is much more frequent than due to HSV-2. |

|||||

Figure 7 Histopathology showing Treponema pallidum spirochetes in testis of experimentally infected rabbit. Modified Steiner silver stain.

CDC/Dr. Edwin P. Ewing, Jr.

epe1@cdc.gov

Figure 7 Histopathology showing Treponema pallidum spirochetes in testis of experimentally infected rabbit. Modified Steiner silver stain.

CDC/Dr. Edwin P. Ewing, Jr.

epe1@cdc.gov

Figure 10

Figure 10Primary syphilis. A vulvar chancre and condylomata acuminata The University of Texas Medical Branch

|

Syphilis Treponema pallidum (figure 7), a spirochete, is a major public health concern because of the complications of untreated disease. In the United States, the rates of primary and secondary syphilis have declined significantly in the past thirty years (figure 20-21). Some racial and ethnic groups such as African Americans, Native Americans and Alaskan natives continue to have disproportionately high rates of syphilis (figure 22). The incidence of primary and secondary syphilis in non-Hispanic blacks remains high at 17 cases per 100,000 persons which is 34 times greater than the rate for non-Hispanic whites. In the U.S., the Southeast has the highest rates of syphilis perhaps due to poor access to health care, unemployment and the stigma associated with discussion of STDs (figure 21). Untreated syphilis infection in pregnancy can lead to congenital syphilis in 70% of the cases. The prevalence of syphilis in HIV infected individuals ranges from 14 to 22%. Syphilis, along with other genital ulcer diseases, facilitates transmission of HIV. A syphilitic chancre not only increases transmission of HIV by causing a breakdown of the skin, but also increases the number of inflammatory cells receptive to HIV. The transmission rate of syphilis from an infected sexual partner has been estimated at 30%. T. pallidum is an exclusive human pathogen that can be visualized by dark field microscopy. It appears as a spiral bacterium with corkscrew motility. After inoculation through abraded skin or mucus membranes it attaches to the host cells and disseminates within a few hours to the regional lymph nodes and eventually to the internal organs and the central nervous system. The clinical presentation of syphilis is divided into primary, secondary, early latent, late latent and tertiary stages based on infectiousness and for purposes of therapeutic decisions and disease-intervention strategies (figure 8).

Diagnosis of syphilis Serological tests are the most widely used tests for syphilis and are categorized into treponemal and non-treponemal tests. The non-treponemal tests detect anti-cardiolipin antibodies and include RPR (Rapid Plasma Reagin), Toluidine Red Unheated Serum Test (TRUST) and Reagin Screen test (RST), VDRL (Venereal Disease Research Laboratory) and Unheated Serum Reagin (USR). The sensitivity of the non-treponemal tests varies from 70% in primary syphilis to 100% in secondary syphilis. These tests are advantageous because they are inexpensive, applicable for screening purposes, and their titers tend to correlate with disease activity. However, confirmation of the non-treponemal tests is necessary with the specific treponemal tests. The FTA-ABS (fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test), the MHA-TP (microhemagglutination assay) and the TP-PA (particle agglutination assay) are 80% to 100% sensitive depending on the stage of disease. However, a positive MHA-TP alone does not establish the diagnosis of primary syphilis in a patient with genital ulcer, since the MHA-TP can remain positive for life. Patients suspected of having primary syphilis with a negative darkfield examination, negative RPR and MHA-TP should have follow up serologies in 2 weeks, since detection by direct microscopy depends on specimen collection and the expertise of the microscopist, and since serologies can be negative in the first two weeks after a chancre appears. False-positive non-treponemal and treponemal tests can occur in a variety of disease conditions including acute viral infections, autoimmune diseases, vaccination, drug addiction and malignancy. Latent syphilis is diagnosed when a patient has a reactive RPR and a confirmatory test in the absence of signs or symptoms. The duration of disease from exposure can be estimated if the patient can recall specific signs or symptoms consistent with primary syphilis, has a history of exposure or previous serology. However, the usual scenario is that of a patient with positive serology and no clinical history suggestive of syphilis. |

|||||

|

|

||||||

Figure 24

Figure 24This direct smear microscopic exam revealed the presence of Haemophilus ducreyi indicative of a chancroid infection. CDC

|

The incidence of chancroid has been steadily decreasing in the US. The disease is endemic in some areas (New York City and Texas) and tends to occur as outbreaks in other parts of the US. Chancroid is a major cause of genital ulcer diseases in the tropics. Haemophilus ducreyi is a gram-negative rod (figure 24) that requires abraded skin to penetrate the epidermis and cause infection. It is spread by sexual contact but autoinoculation of other sites can occur. After an incubation period of 3 to 10 days, a papule surrounded by erythema develops at the site of inoculation (figure 27). The papule evolves to a pustule over 24 to 48 hours and then ulcerates (figure 25-26). Men tend to note significant pain with the ulcer whereas women may not notice the ulcer. About 50% of patients note tender unilateral inguinal adenopathy (buboes). Buboes (figure 29-30) can become fluctuant, undergo spontaneous drainage (figure 28) and result in large ulcers. Systemic symptoms are usually not a feature of chancroid. Chancroid is a clinical diagnosis based on:

The presence of a painful ulcer along with tender lymphadenopathy with suppuration is highly suspicious for chancroid. A definitive diagnosis is made by culture of H. ducreyi but appropriate culture media are not widely available.

|

|||||

Figure 27 A differential diagnosis revealed that this was a chancroidal

lesion, and not a suspected syphilitic lesion, or chancre. CDC

Figure 27 A differential diagnosis revealed that this was a chancroidal

lesion, and not a suspected syphilitic lesion, or chancre. CDC

|

||||||

Figure 31

Figure 31This was a case of trichomonas vaginitis revealing a copious purulent discharge emanating from the cervical os. Trichomonas vaginalis, a flagellate, is the most common pathogenic protozoan of humans in industrialized countries. This protozoan resides in the female lower genital tract and the male urethra and prostate, where it replicates by binary fission. CDC |

Vaginal discharge is a frequent gynecologic complaint, accounting for more than 10 million office visits annually. Physiologic vaginal discharge is white, odorless and increases during midcycle due to estrogen. Abnormal vaginal discharge may result from vaginitis or vaginosis, cervicitis and occasionally endometritis. Vaginitis presents with an increase in the amount, odor or color of discharge and may be accompanied by itching, dysuria, dyspareunia, edema or irritation of the vulva. The three most common causes of vaginal discharge are bacterial vaginosis or BV (40% to 50% of cases; associated with Gardnerella vaginalis and overgrowth of various bacteria including anaerobes), vulvovaginal candidiasis (20% to 25% of cases) and trichomoniasis (figure 31) (15% to 20% of cases). While trichomoniasis is a sexually transmitted disease, bacterial vaginosis occurs in women with high rates of STDs as well as in women who have never been sexually active. Vaginitis may also result from infection with Group A streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus toxic shock syndrome and severe herpes simplex virus infection. Non-infectious causes of vaginal discharge include chemical or irritant vaginitis, trauma, pemphigus, and collagen vascular diseases. Vaginal discharge may result from cervicitis caused by N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis. Severe genital herpes infection can cause both cervicitis and vaginitis.

|

|||||

Figure 32

Figure 32Gonorrhea Rates 1941-2006 CDC

|

Gonorrhea In the United States 355,642 cases of gonorrhea were diagnosed in 1998, the first increase since 1985 (figure 32). This increase is thought to be from expansion of screening programs and improved surveillance, increased sensitivity of new diagnostic tests, and an increase in morbidity. The risk factors for gonorrhea include young age (15- to 19-year- old age group in women and 20- to 24-year old age group in men), low socioeconomic status, early onset of sexual activity, unmarried marital status, past history of gonorrhea and men who have sex with men. Recently, there have been reports of increased incidence of rectal gonorrhea among men who have sex with men. The rates of gonorrhea are highest among minority races such as African-Americans, Hispanics, Asians and Pacific Islanders. The Southeastern region of the U.S. has the highest rates of gonorrhea in the nation. Transmission efficiency of N. gonorrhoeae (figure 33) depends on the anatomic site of infection and the number of sexual exposures. Transmission by penile-vaginal intercourse has been reported to be 50% to 90% among women who are sexual contacts of infected men compared to 20% among men who are sexual contacts of infected women. The latter can increase to 60% to 80% following 4 exposures. Transmission of rectal and pharyngeal gonococcal infection is less well defined, but appears to be relatively efficient. Neisseria gonorrhoeae is almost always sexually transmitted except in cases of neonatal transmission. It causes a spectrum of mucosal diseases including pharyngitis (figure 40), conjunctivitis (figure 35), urethritis, cervicitis and proctitis. It also causes disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI), septic arthritis (figure 34), endocarditis, meningitis and pelvic inflammatory disease. Up to 30% people infected with gonorrhea have concomitant infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. After an incubation period of 1 to 14 days, the classic presentation of gonorrhea in men is the presence of pus at the urethral meatus accompanied by symptoms of dysuria, edema or erythema of the urethral meatus. However, a fourth of the patients may only develop scant, mucoid exudate or no exudate at all. Complications of gonococcal urethritis in men include epididymitis, acute or chronic prostatitis. Men who have sex with men may also have rectal gonorrhea, which is usually asymptomatic but may be associated with tenesmus, discharge and rectal bleeding. Oropharyngeal gonorrhea may manifest as acute pharyngitis or tonsillitis, the large majority of which are asymptomatic. In women, the primary site of infection is the endocervical canal, which may present with purulent or mucopurulent discharge, erythema, edema and friability of the cervix (figure 38). Concurrent urethritis, infection of the periurethral gland (Skene’s gland) or Bartholin’s gland may also be present. Symptoms of gonococcal infection in women may include vaginal discharge, dysuria, menorrhagia or intermenstrual bleeding. However, the majority of women with gonorrhea have few symptoms. Approximately one-third of women with gonococcal cervicitis may also have positive rectal cultures usually due to perineal contamination with gonococci or due to rectal intercourse. About 10% to 20% of women with acute gonorrhea develop acute salpingitis or pelvic inflammatory disease (see section on pelvic inflammatory disease, below). Systemic complications of gonorrhea include perihepatitis (Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome), disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI), endocarditis and rarely meningitis. The incidence of DGI is 0.5% to 3% among patients with untreated gonorrhea. Bacteremia begins 7 to 30 days after infection. In the majority of patients mucosal infection is often asymptomatic which may lead to underdiagnosis of DGI. The most common involvement is the skin and joints (figure 36-37), which leads to arthralgias or arthritis, tenosynovitis, and tender necrotic nodules with an erythematous base in the distal extremities (gonococcal arthritis-dermatitis syndrome). Patients with DGI should also be examined for endocarditis or meningitis. Gonorrhea can also be maternally transmitted (figure 41).

|

|||||

Figure 36 This patient presented with a cutaneous gonococcal

lesion due to a disseminated Neisseria gonorrhea bacterial infection. CDC

Figure 36 This patient presented with a cutaneous gonococcal

lesion due to a disseminated Neisseria gonorrhea bacterial infection. CDC

|

||||||

Figure 42

Figure 42Chlamydia trachomatis taken from a urethral scrape. Untreated, chlamydia can cause severe, costly reproductive and other health problems including both short- and long-term consequences, i.e. pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), infertility, and potentially fatal tubal pregnancy. CDC/ Dr. Wiesner, Dr. Kaufman

|

Chlamydia trachomatis Infection Infections due to C. trachomatis (figure 42) are one of the most prevalent STDs. The rates of chlamydia infection among males and females are highest in the age groups between 15 to 24 years (figure 44). The majority of chlamydia urethritis in men and cervicitis in women are asymptomatic. Women endure the most morbidity and the most costly outcomes of chlamydia infection due to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), ectopic pregnancy, tubal infertility and chronic pelvic pain. In men, chlamydia was formerly considered to be the cause of most cases of non-gonococcal urethritis (NGU) but recent data suggest that only 10% to 20% of cases of NGU are caused by Chlamydia (see section on urethritis in men). Transmissibility of C. trachomatis has not been well studied. However, a recent study has shown that 68% of male partners of infected women and 70% of female partners of infected men are positive by PCR for C. trachomatis suggesting that transmission from men or women is equally efficient. C. trachomatis infects the columnar or squamocolumnar epithelium of the urethra, cervix, rectum, conjunctiva and the respiratory tract (in the neonate). All chlamydiae contain DNA, RNA and cell walls that resemble those of gram-negative bacteria and require multiplication in eukaryotic cells. C. trachomatis causes a spectrum of lower and upper genital tract diseases in women: urethritis, Bartholinitis, cervicitis (figure 43), endometritis, salpingitis, tubo-ovarian abscess, ectopic pregnancy, pelvic peritonitis and perihepatitis (Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome). About 75% to 90% of cases of chlamydial cervicitis are asymptomatic and may persist for years. Among women with gonorrhea, 30% to 50% have concomitant Chlamydia infection. Approximately 40% to 50% of men with chlamydial urethritis may be symptomatic with dysuria or minimal urethral discharge. In 1% of men, urethritis may lead to epididymitis. C. trachomatis serovars L1-3 cause Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV), which is characterized by a genital papule followed by unilateral tender inguinal lymphadenopathy. Other genital ulcer diseases such as syphilis, chancroid or herpes should be considered in the differential diagnosis of LGV. While LGV is common in the tropical countries it is uncommon in the United States.

|

|||||

Figure 44 Chlamydia — Age- and sex-specific rates: United States,

2006

Figure 44 Chlamydia — Age- and sex-specific rates: United States,

2006

|

||||||

Figure 46

Figure 46Generalized peritonitis due to what was diagnosed as a pelvic abscess. A differential diagnosis included pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), which if it had been the root cause, could begin with a pelvic origin, and become disseminated throughout the abdominopelvic cavity, thereby, causing a generalized peritonitis. CDC/ Dr. James Curran |

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) signifies inflammation of the upper female genital tract and its related structures. PID can manifest as endometritis, salpingitis, adnexitis, tubo-ovarian abscess, pelvic peritonitis (figure 46) or perihepatitis. The most common manifestation of PID is salpingitis, and these terms are used synonymously in the literature. PID is one of the most common causes of hospitalization among women of reproductive age. Risk factors for PID include young age, multiple sexual partners, use of intrauterine devices, vaginal douching, tobacco smoking, bacterial vaginosis, HIV infection and STDs with gonorrhea or chlamydia. Use of oral contraceptives has been associated with a decreased rate of PID, especially from infection with C. trachomatis. Most cases of PID are secondary to C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae. C. trachomatis is the most common cause of PID in the United States. C. trachomatis is implicated with the entity of “silent salpingitis” or subclinical PID. Approximately 10% of women with chlamydial cervicitis, and between 10% and 19% of women with gonococcal cervicitis, can develop acute PID. The pathogenesis of PID is not well understood. In advanced cases, numerous bacterial species are typically present as “secondary invaders,” including anaerobes and aerobic “bowel flora” bacteria. The chronic sequelae of chlamydia-induced PID, such as ectopic pregnancy and tubal infertility, are thought to be due to an inflammatory reaction to the chlamydial heat shock protein (HSP-60). Certain characteristics of gonococcal strains such as the serovar, the formation of transparent colonies on agar, and penicillin resistance have been correlated with a propensity for causing tubal infection. Women with PID and gonococcal infection tend to present with pain during the first part of the menstrual cycle suggesting the ascent of gonococci into the upper genital tract through a cervix with scant mucus during the menstrual cycle.

|

|||||

Figure 47

Figure 47This patient presented with a case of non-specific urethritis with accompanying meatitis, and a mucopurulent urethral discharge. Non-specific urethritis merely means that upon presentation, the cause of this given case of urethral inflammation is unknown. A differential diagnostic process will help to narrow the possible causes by ruling out those possibilities that do not provide respective positive test results. CDC |

Urethritis in Males Urethritis (inflammation of the urethra) is characterized by a burning sensation during urination or itching or discharge at the urethral meatus. The exudate (figure 47) may be mucoid, mucopurulent or purulent. Traditionally, urethritis has been differentiated into gonococcal or nongonococcal urethritis. When N. gonorrhoeae cannot be detected, the syndrome is called non-gonococcal urethritis (NGU). In the United States, the rates of NGU have surpassed that of gonococcal urethritis in the past 20 to 30 years. The 20- to 24-year-old age group has the highest incidence of gonococcal and non-gonococcal urethritis. Up to 25% to 30% of men with gonococcal urethritis also have concurrent Chlamydia infection. In the past, the prevalence of C. trachomatis as the cause of NGU has ranged form 23% to 55%. Recent studies showed that up to two-thirds of cases of NGU remain undiagnosed. Ureaplasma urealyticum, Mycoplasma genitalium and occasionally Trichomonas vaginalis and Herpes simplex virus have also been shown to cause NGU. Gonococcal urethritis usually presents with a purulent discharge and dysuria whereas NGU usually presents with a scant, mucoid discharge. However, in some patients the inflammatory exudate may not be apparent on examination. Patients with NGU may have a discharge that is noted only in the morning or as crusting at the meatus or as a stain on the underwear. It is difficult to distinguish gonococcal and non-gonococcal urethritis based on physical examination alone. Patients with gonococcal urethritis present with acute urethritis and usually present within 4 days of onset of symptoms. Patients with non-gonococcal urethritis may present after 1 to 5 weeks after infection. Both groups may have asymptomatic infection. Some patients present with recurrent urethritis characterized by persistent symptoms or frequent recurrences. The symptoms of classic urinary tract infection such as fever, chills, frequency, urgency, hematuria is not a feature of urethritis. Differential diagnosis of cystitis, prostatitis, epididymitis, Reiter’s syndrome and bacterial cystitis should be considered when evaluating a patient with urethritis.

|

|||||

Figure 48

Figure 48This patient presented with chemical dermatitis of the perineum due to her extensive treatment for labial venereal warts. Condylomata acuminata, or genital warts, is a sexually transmitted disease caused by the Human Papilloma Virus, (HPV), which manifests as bumps or warts on the genitalia, or within the perineal region. CDC/JoeMillar

|

Human Papillomavirus Infection Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common viral sexually transmitted disease worldwide. The prevalence ranges from 20% to 46% in young women worldwide. In the U.S., 1% of sexually active persons between the ages of 15 to 49 years are estimated to have genital warts from HPV. The incidence of HPV infection is high among college students (35% to 43%) especially among minority races, individuals with multiple sexual partners and alcohol consumption. Immunocompromised persons including those with HIV infection have increased prevalence of HPV infection. Most genital HPV infections are subclinical and are transmitted primarily through sexual contact. Several transmission studies noted that 75% to 95% of male partners of women with HPV-genital lesions also had genital HPV infection. Vertical transmission can cause laryngeal papillomatosis in infants and children. Digital transmission of genital warts can also occur. Human papillomavirus is a double-stranded DNA virus that infects the squamous epithelium. It causes a spectrum of clinical disease ranging from asymptomatic infection, benign plantar and genital warts (figure 48), squamous intra-epithelial neoplasia (bowenoid papulosis, erythroplasia of Queyart, or Bowen’s disease of the genitalia) and frank malignancy (Buschke-Lowenstein tumor (figure 49), a form of verrucous squamous cell carcinoma) in the anogenital region. External genital warts have various morphological manifestations such as condyloma acuminata (cauliflower-like), smooth dome-shaped papular warts, keratotic warts and flat warts (squamous intra-epithelial neoplasia). Condyloma acuminata tend to occur on moist surfaces while the keratotic and smooth warts occur on fully keratinized skin. Flat warts can occur on either surface. Approximately one hundred types of HPV have been identified. The thirty types that infect the anogenital area can be divided into low-risk (e.g., 6, 11, 42, 43, 44) and high-risk types (e.g., 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 52, 55, 56, 58) based on their association with anogenital cancer. Types 6 and 11 are commonly associated with external genital, cervical, vaginal, urethral and anal warts as well as conjunctival, nasal, oral and laryngeal warts. While HPV types 6 and 11 are found in 90% of condyloma acuminata, they are rarely associated with squamous cell carcinoma of the external genitalia. On the other hand, HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35 have been associated with malignant transformation, squamous intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva, vagina, cervix, penis and anus. About 95% of squamous cell carcinomas of the cervix contain HPV-DNA. Most HPV infections do not cause any clinical manifestations and mixed types can be found in each lesion. Most genital warts are asymptomatic but they may cause itching, burning, pain and bleeding. Condyloma acuminata (figure 50) can present as multiple nodules or large, exophytic, pedunculated, cauliflower like lesions in the anogenital area. They are usually noted on the penis, vulva, vagina, cervix, perineum and the anal region. Flat condylomas are usually subclinical and not visible to the naked eye. They are most commonly noted on the cervix, but may also be present on the vulva and the penis. They may also present as white plaque like lesions in the anogenital region.

|

|||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||