|

x |

x |

|

|

|

|

INFECTIOUS

DISEASE |

BACTERIOLOGY |

IMMUNOLOGY |

MYCOLOGY |

PARASITOLOGY |

VIROLOGY |

|

|

PARASITOLOGY - CHAPTER FOUR

NEMATODES (Round Worms)

Dr

Abdul

Ghaffar

Professor Emeritus

University of South Carolina

|

|

|

|

SHQIP - ALBANIAN |

Let us know what you think

FEEDBACK |

|

SEARCH |

|

|

|

|

Logo image © Jeffrey

Nelson, Rush University, Chicago, Illinois and

The MicrobeLibrary |

|

Reading: Medical Microbiology, Murray et

al. (6th ed.), chapter 83

All

life cycle diagrams in this section are courtesy of the

DPDx Parasite

Image Library

Centers for Disease Control (CDC)

TEACHING

OBJECTIVES

Epidemiology, morbidity and

mortality

Morphology of the organism

Life cycle, hosts and vectors

Disease, symptoms,

pathogenesis and site

Diagnosis

Prevention and control |

INTESTINAL HELMINTHS

Intestinal nematodes of importance to

man are:

-

Ascaris lumbricoides (roundworm)

-

Trichinella spiralis

(trichinosis)

-

Trichuris trichiura (whipworm)

-

Enterobius vermicularis

(pinworm)

-

Strongyloides stercoralis (Cochin-china diarrhea)

-

Ancylostoma

duodenale and Necator americanes (hookworms)

-

Dracunculus

medinensis (fiery serpents of the Israelites).

E. vermicularis and T. trichiura

are exclusively intestinal parasites. Other helminths listed above have both

intestinal and tissue phases.

|

Figure 1

Figure 1

Ascaris Life Cycle

Adult worms

live in

the lumen of the small intestine. A female may produce

approximately 200,000 eggs per day, which are passed with the feces live in

the lumen of the small intestine. A female may produce

approximately 200,000 eggs per day, which are passed with the feces

.

Unfertilized eggs may be ingested but are not infective. Fertile

eggs embryonate and become infective after 18 days to several weeks .

Unfertilized eggs may be ingested but are not infective. Fertile

eggs embryonate and become infective after 18 days to several weeks

,

depending on the environmental conditions (optimum: moist, warm, shaded

soil). After infective eggs are swallowed ,

depending on the environmental conditions (optimum: moist, warm, shaded

soil). After infective eggs are swallowed

,

the larvae hatch ,

the larvae hatch

,

invade the intestinal mucosa, and are carried via the portal, then

systemic circulation to the lungs ,

invade the intestinal mucosa, and are carried via the portal, then

systemic circulation to the lungs

.

The larvae mature further in the lungs (10 to 14 days), penetrate

the alveolar walls, ascend the bronchial tree to the throat, and are

swallowed .

The larvae mature further in the lungs (10 to 14 days), penetrate

the alveolar walls, ascend the bronchial tree to the throat, and are

swallowed

. Upon

reaching the small intestine, they develop into adult worms . Upon

reaching the small intestine, they develop into adult worms

.

Between 2 and 3 months are required from ingestion of the

infective eggs to oviposition by the adult female. Adult worms can

live 1 to 2 years. .

Between 2 and 3 months are required from ingestion of the

infective eggs to oviposition by the adult female. Adult worms can

live 1 to 2 years.

CDC

|

|

WEB RESOURCES

Many

images on this page come from the Parasite

Image Library

CDC

|

Ascaris lumbricoides

(Large intestinal roundworm)

Epidemiology

The annual global morbidity due to ascaris infections is estimated at 1 billion with a mortality of

20,000. Ascariasis can occur at all ages, but it is more prevalent in the 5 to 9 years

age group. The incidence is higher in poor rural populations.

Morphology

The average female worm measures 30 cm x 5 mm. The male is smaller.

Life cycle (figure 1)

The infection occurs by ingestion of food contaminated with infective eggs which

hatch in the upper small intestine. The larvae (250 x 15 micrometers) penetrate the

intestinal wall and enter the venules or lymphatics. The larvae pass through the

liver, heart and lung to reach alveoli in 1 to 7 days during which period they grow

to 1.5 cm. They migrate up the bronchi, ascend the trachea to the glottis, and

pass down the esophagus to the small intestine where they mature in 2 to 3 months.

A female may live in the intestine for 12 to 18 months and has a capacity of

producing 25 million eggs at an average daily output of 200,000 (figure 2). The eggs are

excreted in feces, and under suitable conditions (21 to 30 degrees C, moist, aerated

environment) infective larvae are formed within the egg. The eggs are resistant

to chemical disinfectant and survive for months in sewage, but are killed by

heat (40 degrees C for 15 hours). The infection is man to man. Auto

infection can occur.

Symptoms

Symptoms are related to the worm burden. Ten to twenty worms may go unnoticed except

in a routine stool examination. The commonest complaint is vague abdominal pain.

In more severe cases, the patient may experience listlessness, weight loss,

anorexia, distended abdomen, intermittent loose stool and occasional vomiting.

During the pulmonary stage, there may be a brief period of cough, wheezing,

dyspnea and sub-sternal discomfort. Most symptoms are due to the physical presence

of the worm.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on identification of eggs (40 to 70

micrometers by 35 to 50 micrometers - figure 2) in

the stool.

Treatment and Prevention

Mebendazole, 200 mg, for adults and 100 mg for children, for 3 days is

effective. Good hygiene is the best preventive measure.

|

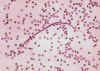

| Figure 2

A fertilized Ascaris egg, still at the unicellular stage, as

they are when passed in stool. Eggs are normally at this stage when passed in the stool (Complete development of the larva requires 18 days under favorable conditions).

CDC DPDx

Parasite Image Library

A fertilized Ascaris egg, still at the unicellular stage, as

they are when passed in stool. Eggs are normally at this stage when passed in the stool (Complete development of the larva requires 18 days under favorable conditions).

CDC DPDx

Parasite Image Library |

Eggs, unfertilized (left) and fertilized (right). Patient seen in Haiti.

Eggs, unfertilized (left) and fertilized (right). Patient seen in Haiti.

CDC DPDx

Parasite Image Library |

Unfertilized egg. Prominent mamillations of outer layer. Ten-year old boy seen in Cherokee, North Carolina.

Unfertilized egg. Prominent mamillations of outer layer. Ten-year old boy seen in Cherokee, North Carolina.

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library

Fertilized egg. The embryo can be distinguished inside the egg.

Ten-year old boy seen in Cherokee, North Carolina.

Fertilized egg. The embryo can be distinguished inside the egg.

Ten-year old boy seen in Cherokee, North Carolina.

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library

Unfertilized egg with no outer mamillated layer (decorticated). Patient seen during a survey in Bolivia.

Unfertilized egg with no outer mamillated layer (decorticated). Patient seen during a survey in Bolivia.

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library

Two fertilized eggs from the same patient, where embryos have begun to develop (this happens when the stool sample is not processed for several days

without refrigeration). The embryos in early stage of division (4-6 cells) can be clearly seen. Note that the egg on the left has a very thin mamillated outer layer.

Two fertilized eggs from the same patient, where embryos have begun to develop (this happens when the stool sample is not processed for several days

without refrigeration). The embryos in early stage of division (4-6 cells) can be clearly seen. Note that the egg on the left has a very thin mamillated outer layer.

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library

Larva hatching from an egg.

Larva hatching from an egg.

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library

An adult Ascaris worm. Diagnostic characteristics: tapered ends; length 15-35 cm (the females tend to be the larger ones). This worm is a female, as

evidenced by the size and genital girdle (the dark circular groove at bottom area

of image). Worm passed by a female child in Florida.

An adult Ascaris worm. Diagnostic characteristics: tapered ends; length 15-35 cm (the females tend to be the larger ones). This worm is a female, as

evidenced by the size and genital girdle (the dark circular groove at bottom area

of image). Worm passed by a female child in Florida.

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library

Ascaris lumbricoides adult male and female

Ascaris lumbricoides adult male and female

©

Dr

Peter Darben, Queensland University of Technology clinical

parasitology collection. Used with permission

Ascaris lumbricoides larva in section of lung (H&E)

Ascaris lumbricoides larva in section of lung (H&E)

©

Dr Peter

Darben, Queensland University of Technology clinical parasitology

collection. Used with permission

|

Egg containing a larva, which will be infective if ingested. Patient seen in

Léogane, Haiti.

Egg containing a larva, which will be infective if ingested. Patient seen in

Léogane, Haiti.

CDC DPDx

Parasite Image Library |

|

Figure 3

Trichinellosis

is acquired by ingesting meat containing cysts (encysted larvae) Trichinellosis

is acquired by ingesting meat containing cysts (encysted larvae)

of Trichinella. After exposure to gastric acid and pepsin,

the larvae are released

of Trichinella. After exposure to gastric acid and pepsin,

the larvae are released

from the cysts and invade the small bowel mucosa where they develop into

adult worms

from the cysts and invade the small bowel mucosa where they develop into

adult worms  (female

2.2 mm in length, males 1.2 mm; life span in the small bowel: 4 weeks).

After 1 week, the females release larvae (female

2.2 mm in length, males 1.2 mm; life span in the small bowel: 4 weeks).

After 1 week, the females release larvae

that migrate to the striated muscles where they encyst

that migrate to the striated muscles where they encyst

.

Trichinella pseudospiralis, however, does not encyst.

Encystment is completed in 4 to 5 weeks and the encysted larvae may

remain viable for several years. Ingestion of the encysted larvae

perpetuates the cycle. Rats and rodents are primarily responsible

for maintaining the endemicity of this infection.

Carnivorous/omnivorous animals, such as pigs or bears, feed on infected

rodents or meat from other animals. Different animal hosts are

implicated in the life cycle of the different species of Trichinella.

Humans are accidentally infected when eating improperly processed meat

of these carnivorous animals (or eating food contaminated with such

meat). .

Trichinella pseudospiralis, however, does not encyst.

Encystment is completed in 4 to 5 weeks and the encysted larvae may

remain viable for several years. Ingestion of the encysted larvae

perpetuates the cycle. Rats and rodents are primarily responsible

for maintaining the endemicity of this infection.

Carnivorous/omnivorous animals, such as pigs or bears, feed on infected

rodents or meat from other animals. Different animal hosts are

implicated in the life cycle of the different species of Trichinella.

Humans are accidentally infected when eating improperly processed meat

of these carnivorous animals (or eating food contaminated with such

meat).

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library |

Trichinella

spiralis (Trichinosis)

Epidemiology

Trichinosis is related to the quality of pork and consumption of poorly cooked

meat. Autopsy surveys indicate about 2 percent of the population is infected. The

mortality rate is low.

Morphology

The adult female measures 3.5 mm x 60 micrometers. The larvae in the tissue (100 micrometers x 5 micrometers) are coiled in a lemon-shaped capsule.

Life cycle

Infection occurs by ingestion of larvae, in poorly cooked meat, which

immediately invade intestinal mucosa and sexually differentiate within 18 to 24

hours. The female, after fertilization, burrows deeply in the small intestinal

mucosa, whereas the male is dislodged (intestinal stage). On about the 5th day

eggs begin to hatch in the female worm and young larvae are deposited in the mucosa

from where they reach the lymphatics, lymph nodes and the blood stream (larval

migration). Larval dispersion occurs 4 to 16 weeks after infection. The larvae are

deposited in muscle fiber and, in striated muscle, they form a capsule which

calcifies to form a cyst. In non-striated tissue, such as heart and brain,

the larvae do not calcify; they die and disintegrate. The cyst may persist for

several years. One female worm produces approximately 1500 larvae. Man is the

terminal host. The reservoir includes most carnivorous and omnivorous animals

(Figure 3 and 4).

Symptoms

Trichinosis symptoms depend on the severity of infection: mild infections may be

asymptomatic. A larger bolus of infection produces symptoms according to the

severity and stage of infection and organs involved (Table 1).

Pathology and

Immunology

Trichinella pathogenesis is due the presence of large numbers

of larvae in vital muscles and host reaction to larval metabolites. The muscle

fibers become enlarged edematous and deformed. The paralyzed muscles are

infiltrated with neutrophil, eosinophils and lymphocytes.

Splenomegaly is

dependent on the degree of infection. The worm induces a strong IgE response

which, in association with eosinophils, contributes to parasite death.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on symptoms, recent history of eating raw or undercooked meat

and laboratory findings (eosinophilia, increased serum creatine phosphokinase

and lactate dehydrogenase and antibodies to T. spiralis).

Treatment and

Control

Steroids are use for treatment of inflammatory symptoms and

Mebendazole is used to eliminate worms. Elimination of parasite infection in

hogs and adequate cooking of meat are the best ways of avoiding infection.

|

| |

Figure

4

Encysted larvae of Trichinella in pressed muscle tissue. The coiled larvae can be seen inside the cysts.

Encysted larvae of Trichinella in pressed muscle tissue. The coiled larvae can be seen inside the cysts.

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library

Larvae of Trichinella, freed from their cysts, typically coiled; length: .8 to 1 mm. Alaskan bear.

Larvae of Trichinella, freed from their cysts, typically coiled; length: .8 to 1 mm. Alaskan bear.

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library

Trichinella spiralis larvae in muscle section (H&E) and muscle press

Trichinella spiralis larvae in muscle section (H&E) and muscle press

©

Dr

Peter Darben, Queensland University of Technology clinical

parasitology collection. Used with permission

|

| |

|

Table 1

Trichinosis symptomatology |

|

Intestinal mucosa

(24-72 hrs) |

Circulation and

muscle

(10-21 days) |

Myocardium

(10-21 days) |

Brain and meninges

(14-28 days) |

|

Nausea, vomiting

diarrhea, abdominal pain, headache. |

Edema, peri-orbital

conjunctivitis, photo phobia, fever, chill, sweating, muscle pain,

spasm, eosinophilia. |

Chest pain,

tachycardia, EKG changes, edema of extremities, vascular thrombosis. |

Headache (supraorbital),

vertigo, tinnitus, deafness, mental apathy, delirium, coma, loss of

reflexes. |

|

| Figure 5

Life cycle of Trichuris trichiura

Life cycle of Trichuris trichiura

The unembryonated

eggs are passed with the stool (1). In the soil, the eggs develop

into a 2-cell stage (2), an advanced cleavage stage (3), and then they

embryonate (4); eggs become infective in 15 to 30 days. After

ingestion (soil-contaminated hands or food), the eggs hatch in the small

intestine, and release larvae (5) that mature and establish themselves

as adults in the colon (6). The adult worms (approximately 4 cm in

length) live in the cecum and ascending colon. The adult worms are

fixed in that location, with the anterior portions threaded into the

mucosa. The females begin to oviposit 60 to 70 days after

infection. Female worms in the cecum shed between 3,000 and 20,000

eggs per day. The life span of the adults is about 1 year.

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library |

Trichuris trichiura

(whipworm)

Epidemiology

Trichuriasis is a tropical disease of children (5 to 15 yrs) in rural Asia (65% of

the 500 - 700 million cases). It is, however, seen in the two Americas, mostly in

the South and is concentrated in families and groups with poorer sanitary

habits.

Morphology

The female organism is 50 mm long with a slender anterior (100

micrometer dia,eter) and

a thicker (500 micrometers diameter) posterior end. The male is smaller and has a coiled

posterior end. The Trichuris eggs are lemon or football shaped and have terminal

plugs at both ends.

Life cycle

Infection occurs by ingestion of embryonated eggs in soil. The larva escapes the

shell in the upper small intestine and penetrates the villus where it remains

for 3 to 10 days. Upon reaching adolescence, the larvae pass to the cecum and embed

in the mucosa. They reach the ovipositing age in 30 to 90 days from infection,

produce 3000 to 10,000 eggs per day and may live as long as 5 to 6 years. Eggs passed

in feces embryonate in moist soil within 2 to 3 weeks (Figure 5 and 6). The eggs are less

resistant to desiccation, heat and cold than ascaris eggs. The embryo is killed

under desiccation at 37 degrees C within 15 minutes. Temperatures of 52 degrees C and -9

degrees C are

lethal.

Symptoms

Symptoms are determined largely by the worm burden: less than 10 worms are

asymptomatic. Heavier infections (e.g., massive infantile trichuriasis) are

characterized by chronic profuse mucus and bloody diarrhea with abdominal pains

and edematous prolapsed rectum. The infection may result in malnutrition, weight

loss and anemia and sometimes death.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on symptoms and the presence of eggs in feces

(50 to 55 x 20 to 25 micrometers).

Treatment and

Control

Mebendazole, 200 mg, for adults and 100 mg for children, for 3

days is effective. Accompanying infections must be treated accordingly. Improved

hygiene and sanitary eating habits are most effective in control.

|

| |

Figure

6

Egg of Trichuris trichuria as seen on wet mount. The diagnostic

characteristics are:

a typical barrel shape two polar plugs, that are unstained size: 50-54 µm by 22-23 µm.

The external layer of the shell of the egg is yellow-brown (in contrast to the clear polar plugs). The egg is

unembryonated, as eggs are when passed with the stool.

Egg of Trichuris trichuria as seen on wet mount. The diagnostic

characteristics are:

a typical barrel shape two polar plugs, that are unstained size: 50-54 µm by 22-23 µm.

The external layer of the shell of the egg is yellow-brown (in contrast to the clear polar plugs). The egg is

unembryonated, as eggs are when passed with the stool.

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library

Trichuris trichiura adult male and female

Trichuris trichiura adult male and female

©

Dr

Peter Darben, Queensland University of Technology clinical

parasitology collection. Used with permission

Trichuris trichiura eggs, unstained and haematoxylin stained

Trichuris trichiura eggs, unstained and haematoxylin stained

©

Dr Peter

Darben, Queensland University of Technology clinical parasitology

collection. Used with permission

|

| Figure 7

Life cycle of enterobius vermicularis

Life cycle of enterobius vermicularis

Eggs are deposited

on perianal folds (1). Self-infection

occurs by transferring infective eggs to the mouth with hands that have

scratched the perianal area (2).

Person-to-person transmission can also occur through handling of

contaminated clothes or bed linens. Enterobiasis may also be

acquired through surfaces in the environment that are contaminated with

pinworm eggs (e.g., curtains, carpeting). Some small number of

eggs may become airborne and inhaled. These would be swallowed and

follow the same development as ingested eggs. Following ingestion

of infective eggs, the larvae hatch in the small intestine (3)

and the adults establish themselves in the colon (4).

The time interval from ingestion of infective eggs to oviposition by the

adult females is about one month. The life span of the adults is

about two months. Gravid females migrate nocturnally outside the

anus and oviposit while crawling on the skin of the perianal area (5).

The larvae contained inside the eggs develop (the eggs become infective)

in 4 to 6 hours under optimal conditions (1).

Retroinfection, or the migration of newly hatched larvae from the anal

skin back into the rectum, may occur but the frequency with which this

happens is unknown.

CDC |

Enterobius vermicularis

(pinworm)

Epidemiology

Enterobiasis is by far the commonest helminthic infection in the US

(18 million cases at any given time). The worldwide infection is about 210 million. It is an urban disease

of children in crowded environment (schools, day care centers, etc.). Adults may

get it from their children. The incidence in whites is much higher than in

blacks.

Morphology

The female worm measures 8 mm x 0.5mm; the male is smaller. Eggs (60

micrometers x 27 micrometers) are ovoid but asymmetrically flat on one side.

Life cycle

Infection occurs when embryonated eggs are ingested from the environment, with

food or by hand to mouth contact. The embryonic larvae hatch in the duodenum and

reach adolescence in jejunum and upper ilium. Adult worms descend into lower

ilium, cecum and colon and live there for 7 to 8 weeks. The gravid females,

containing more than 10,000 eggs migrate, at night, to the perianal region and

deposit their eggs there. Eggs mature in an oxygenated, moist environment and are

infectious 3 to 4 hours later. Man-to-man and auto infection are common (Figure 7

and 8).

Man is the only host.

Symptoms

Enterobiasis is relatively innocuous and rarely produces serious lesions. The

most common symptom is perianal, perineal and vaginal irritation caused by the

female migration. The itching results in insomnia and restlessness. In some

cases gastrointestinal symptoms (pain, nausea, vomiting, etc.) may develop. The

conscientious housewife's mental distress, guilt complex, and desire to conceal

the infection from her friends and mother-in-law is perhaps the most important

trauma of this persistent, pruritic parasite.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made by finding the adult worm or eggs in the perianal area,

particularly at night. Scotch tape or a pinworm paddle is used to obtain eggs.

Treatment and Control

Two doses (10 mg/kg; maximum of 1g each) of Pyrental Pamoate two weeks apart

gives a very high cure rate. Mebendazole is an alternative. The whole family

should be treated, to avoid reinfection. Bedding and underclothing must be

sanitized between the two treatment doses. Personal cleanliness provides the

most effective in prevention.

|

| |

Figure

8

Enterobius vermicularis adult male and female

©

Dr Peter

Darben, Queensland University of Technology clinical parasitology

collection. Used with permission

Enterobius vermicularis adults in section of appendix (H&E)

©

Dr

Peter Darben, Queensland University of Technology clinical

parasitology collection. Used with permission

A

B

B

C

C

Three eggs of Enterobius vermicularis collected from the same patient on a Swube tube (paddle coated with adhesive material), examined directly on bright field. The diagnostic characteristics are: size 50-60 µm by 20-32 µm; typical elongated shape, with one convex side and one flattened side; colorless shell (here seen as a halo around the egg). The egg in A contains an embryo, while those in B and C contain more differentiated larvae, which are typically coiled.

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library

|

| Figure

9

The Strongyloides life cycle is complex among helminths with its

alternation between free-living and parasitic cycles, and its potential

for autoinfection and multiplication within the host. Two types of

cycles exist:

The Strongyloides life cycle is complex among helminths with its

alternation between free-living and parasitic cycles, and its potential

for autoinfection and multiplication within the host. Two types of

cycles exist:

Free-living cycle: The rhabditiform larvae passed in the stool (1) (see

"Parasitic cycle" below) can either molt twice and become

infective filariform larvae (direct development) (6) or molt four times

and become free living adult males and females (2) that mate and produce

eggs (3) from which rhabditiform larvae hatch (4). The latter in

turn can either develop (5) into a new generation of free-living adults

(as represented in (2)), or into infective filariform larvae (6).

The filariform larvae penetrate the human host skin to initiate the

parasitic cycle (see below) (6).

Parasitic cycle: Filariform larvae in contaminated soil penetrate the

human skin (6), and are transported to the lungs where they penetrate

the alveolar spaces; they are carried through the bronchial tree to the

pharynx, are swallowed and then reach the small intestine (7). In

the small intestine they molt twice and become adult female worms (8).

The females live threaded in the epithelium of the small intestine and

by parthenogenesis produce eggs (9), which yield rhabditiform larvae.

The rhabditiform larvae can either be passed in the stool (1) (see

"Free-living cycle" above), or can cause autoinfection (10).

In autoinfection, the rhabditiform larvae become infective filariform

larvae, which can penetrate either the intestinal mucosa (internal

autoinfection) or the skin of the perianal area (external autoinfection);

in either case, the filariform larvae may follow the previously

described route, being carried successively to the lungs, the bronchial

tree, the pharynx, and the small intestine where they mature into

adults; or they may disseminate widely in the body. To date,

occurrence of autoinfection in humans with helminthic infections is

recognized only in Strongyloides stercoralis and Capillaria

philippinensis infections. In the case of Strongyloides,

autoinfection may explain the possibility of persistent infections for

many years in persons who have not been in an endemic area and of

hyperinfections in immunodepressed individuals

CDC DPDx

Parasite Image Library |

Strongyloides

stercoralis

(Threadworm)

Epidemiology

Threadworm infection, also known as Cochin-China diarrhea, estimated at 50

to 100 million cases worldwide, is an infection of the tropical and subtropical areas with poor

sanitation. In the United States, it is prevalent in the South and among Puerto Ricans.

Morphology

The size and shape of threadworm varies depending on whether it is parasitic or

free-living. The parasitic female is larger (2.2 mm x 45 micrometers) than the

free-living worm (1 mm x 60 micrometers) (figure 10). The eggs, when laid are 55 micrometers by 30 micrometers.

Life cycle

(figure

9)

The infective larvae of S. stercoralis penetrate the skin of man, enter

the venous circulation and pass through the right heart to lungs, where they

penetrate into the alveoli. From there, the adolescent parasites ascend to the

glottis, are swallowed, and reach the upper part of the small intestine, where

they develop into adults. Ovipositing females develop in 28 days from infection.

The eggs in the intestinal mucosa, hatch and develop into

rhabditiform larvae in

man. These larvae can penetrate through the mucosa and cycle back into the blood

circulation, lung, glottis and duodenum and jejunum; thus they continue the auto

infection cycle. Alternatively, they are passed in the feces, develop into

infective filariform larvae and enter another host to complete the direct cycle.

If no suitable host is found, the larvae mature into free-living worm and lay

eggs in the soil. The eggs hatch in the soil and produce rhabditiform larvae

which develop into infective filariform larvae and enter a new host

(indirect cycle), or mature into adult worms to repeat the free-living cycle.

Symptoms

Light infections are asymptomatic. Skin penetration causes itching and red

blotches. During migration, the organisms cause bronchial verminous pneumonia and, in the

duodenum, they cause a burning mid-epigastric pain and tenderness accompanied by

nausea and vomiting. Diarrhea and constipation may alternate. Heavy, chronic

infections result in anemia, weight loss and chronic bloody dysentery. Secondary

bacterial infection of damaged mucosa may produce serious complications.

Diagnosis

The presence of free rhabditiform larvae (figure 10) in the feces is diagnostic. Culture of

stool for 24 hours will produce filariform larvae.

Treatment and

control

Ivermectin or thiabendozole can be used effectively. Direct and

indirect infections are controlled by improved hygiene and auto-infection is

controlled by chemotherapy.

|

Figure 10

Strongyloides stercoralis The esophageal structure is clearly visible in this larva; it consists of a

club-shaped anterior portion; a post-median constriction; and a posterior bulbus

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library

Strongyloides stercoralis

Note the prominent genital primordium in the mid-section of the larva; note also the Entamoeba coli cyst near the tail of the larva.

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library

Strongyloides stercoralis rhabditiform larva

©

Dr Peter

Darben, Queensland University of Technology clinical parasitology

collection. Used with permission

|

| Figure

11

Hookworm life cycle.

Hookworm life cycle.

Eggs are passed in the stool (1), and under favorable conditions

(moisture, warmth, shade), larvae hatch in 1 to 2 days. The

released rhabditiform larvae grow in the feces and/or the soil (2), and

after 5 to 10 days (and two molts) they become become filariform

(third-stage) larvae that are infective (3). These infective

larvae can survive 3 to 4 weeks in favorable environmental conditions.

On contact with the human host, the larvae penetrate the skin and are

carried through the veins to the heart and then to the lungs. They

penetrate into the pulmonary alveoli, ascend the bronchial tree to the

pharynx, and are swallowed (4). The larvae reach the small

intestine, where they reside and mature into adults. Adult worms

live in the lumen of the small intestine, where they attach to the

intestinal wall with resultant blood loss by the host (5). Most

adult worms are eliminated in 1 to 2 years, but longevity records can

reach several years.

Some A. duodenale larvae, following penetration of the host skin,

can become dormant (in the intestine or muscle). In addition,

infection by A. duodenale may probably also occur by the oral and

transmammary route. N. americanus, however, requires a

transpulmonary migration phase.

CDC DPDx

Parasite Image Library

|

Necator americanes

and Ancylostoma duodenale (Hookworms)

Epidemiology

Hookworms parasitize more than 900 million people worldwide and cause daily blood loss of

7 million liters. Ancylostomiasis is the most prevalent hookworm infection and

is second only to ascariasis in infections by parasitic worms. N. americanes (new world hookworm) is most common in the

Americas, central and southern Africa, southern Asia, Indonesia, Australia and

Pacific Islands. A. duodenale (old world hookworm) is the dominant

species in the Mediterranean region and northern Asia.

Morphology

Adult female hookworms are about 11 mm x 50 micrometers. Males are smaller. The anterior

end of N. americanes is armed with a pair of curved cutting plates

whereas A. duodenale is equipped with one or more pairs of teeth.

Hookworm eggs are 60 micrometers x 35 micrometers.

Life cycle

(figure 11 and 12)

The life cycle of hookworms is identical to that of threadworms, except that

hookworms are not capable of a free-living or auto-infectious cycle.

Furthermore, A. duodenale can infect also by oral route.

Symptoms

Symptoms of hookworm infection depend on the site

at which the worm is present (Table 2)

and the burden of worms. Light infection may not be noticed.

|

Table 2.

Clinical features of hookworm disease |

|

Site |

Symptoms |

Pathogenesis |

|

Dermal |

Local erythema,

macules, papules (ground itch) |

Cutaneous invasion

and subcutaneous migration of larva |

|

Pulmonary |

Bronchitis,

pneumonitis and, sometimes, eosinophilia |

Migration of larvae

through lung, bronchi, and trachea |

|

Gastro- intestinal |

Anorexia, epigastric

pain and gastro-intestinal hemorrhage |

Attachment of adult

worms and injury to upper intestinal mucosa |

|

Hematologic |

Iron deficiency,

anemia, hypoproteinemia, edema, cardiac failure |

Intestinal blood loss |

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made by identification of hookworm eggs in fresh or preserved

feces. Species of hookworms cannot be distinguished by egg morphology.

Treatment and

control

Mebendazole, 200 mg, for adults and 100 mg for children, for 3

days is effective. Sanitation is the chief method of control: sanitary disposal

of fecal material and avoidance of contact with infected fecal material.

|

|

|

Figure 12

Hookworm eggs examined on wet mount (eggs of Ancylostoma duodenale and

Necator americanus cannot be distinguished morphologically). Diagnostic characteristics:

Size 57-76 µm by 35-47 µm, oval or ellipsoidal shape, thin shell. The embryo in B has begun cellular division and is at an early (gastrula) developmental stage.

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library

Ancylostoma duodenale adult male and female

©

Dr Peter

Darben, Queensland University of Technology clinical parasitology

collection. Used with permission

Necator americanus adult female, anterior end

©

Dr Peter

Darben, Queensland University of Technology clinical parasitology

collection. Used with permission

Necator americanus adult female, anterior and posterior ends

©

Dr Peter

Darben, Queensland University of Technology clinical parasitology

collection. Used with permission

Hookworm filariform larvae

©

Dr Peter

Darben, Queensland University of Technology clinical parasitology

collection. Used with permission

Necator americanus adult male, posterior end

©

Dr Peter

Darben, Queensland University of Technology clinical parasitology

collection. Used with permission

Hookworm eggs

©

Dr Peter

Darben, Queensland University of Technology clinical parasitology

collection. Used with permission

|

| |

Dracunculus medinensis

(Guinea worm; Fiery serpent)Dracunculiasis comes from the

Latin: affliction with little dragons. The common name "Guinea

worm" results from the first observation of this parasite by Europeans

in the Guinea coast of West Africa in the 17th century. Infection causes

a burning, painful sensation leading to the disease being called the

fiery serpent.

|

|

WEB

RESOURCES

Drancunculis

Guinea Worm - CDC |

Epidemiology

There have been dramatic efforts to eradicate

Dracunculus. CDC

estimated that in 1986 there were 3.5 million cases worldwide. However, at the

end of 2007, there were fewer than 10,000 reported cases in five nations in

Africa: Sudan, Ghana, Nigeria, Niger, and Mali, and as of June 2008, cases had

been reduced by more than 50 percent compared to the same period of 2007. Guinea

worm disease is expected to be the next disease after smallpox to be eradicated

and in 2016 there were probably as few as 25 cases worldwide. There are three

counties in which the disease is still found: Chad, Ethiopia and South

Sudan.

| Year |

Number of reported cases |

Number of countries with reported cases |

| 1989 |

892,055 |

16 |

| 2000 |

75,223 |

16 |

| 2005 |

10,674 |

12 |

| 2010 |

1,797 |

6 |

| 2012 |

542 |

4 |

| 2015 |

22 |

4 |

| 2016 |

25 |

3 |

Morphology

The adult female worm measures 50-120 cm by 1 mm and the male is half

that size.

Life cycle

The infection is caused by ingestion of water contaminated with water fleas

(Cyclops) infected with larvae. The rhabtidiform larvae penetrate the human

digestive tract wall, lodge in the loose connective tissues and mature into the adult

form in 10 to 12 weeks. In about a year, the gravid female migrates to the

subcutaneous tissue of organs that normally come in contact with water and

discharges its larvae into the water (figure 13A). The larvae are picked up by Cyclops, in which

they develop into infective form in 2 to 3 weeks.

Symptoms

If the worm does not reach the skin, it dies and causes little reaction. In

superficial tissue, it liberates a toxic substance that produces a local

inflammatory reaction in the form of a sterile blister with serous exudation.

The worm lies in a subcutaneous tunnel with its posterior end beneath the

blister, which contains clear yellow fluid. The course of the tunnel is marked

with induration and edema. Contamination of the blister produces abscesses,

cellulitis, extensive ulceration and necrosis.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made from the local blister, worm or larvae. The outline of the

worm under the skin may be revealed by reflected light.

Treatment

Treatment includes the extraction of the adult guinea worm by rolling it a few

centimeters per day or preferably by multiple surgical incisions under local

anaesthesia. No drug is effective at killing the worm and there is no vaccine. Protection of

drinking water from being contaminated with Cyclops and larvae are effective

preventive measures and these have led to a dramatic decline in the incidence of

guinea worm infections.

|

| Figure 13

A

B

A, B: The female guinea worm induces a painful blister (A); after rupture of the blister, the worm emerges as a whitish filament (B) in the center of a painful ulcer which is often secondarily infected. (Images contributed by Global 2000/The Carter Center, Atlanta, Georgia).

A, B: The female guinea worm induces a painful blister (A); after rupture of the blister, the worm emerges as a whitish filament (B) in the center of a painful ulcer which is often secondarily infected. (Images contributed by Global 2000/The Carter Center, Atlanta, Georgia).

CDC

C

Dracunculus medinensis

worm wound around matchstick.This helminth is gradually withdrawn from

the body by winding the stick

CDC/Dr. Myron Schultz |

| |

Figure 13A

Figure 13A

Humans become infected by drinking unfiltered water containing copepods (small

crustaceans) which are infected with larvae of D. medinensis

.

Following ingestion, the copepods die and release the larvae, which penetrate

the host stomach and intestinal wall and enter the abdominal cavity and

retroperitoneal space .

Following ingestion, the copepods die and release the larvae, which penetrate

the host stomach and intestinal wall and enter the abdominal cavity and

retroperitoneal space

. After

maturation into adults and copulation, the male worms die and the females

(length: 70 to 120 cm) migrate in the subcutaneous tissues towards the skin

surface . After

maturation into adults and copulation, the male worms die and the females

(length: 70 to 120 cm) migrate in the subcutaneous tissues towards the skin

surface  . Approximately one

year after infection, the female worm induces a blister on the skin, generally

on the distal lower extremity, which ruptures. When this lesion comes into

contact with water, a contact that the patient seeks to relieve the local

discomfort, the female worm emerges and releases larvae . Approximately one

year after infection, the female worm induces a blister on the skin, generally

on the distal lower extremity, which ruptures. When this lesion comes into

contact with water, a contact that the patient seeks to relieve the local

discomfort, the female worm emerges and releases larvae

.

The larvae are ingested by a copepod .

The larvae are ingested by a copepod

and after two weeks (and two molts) have developed into infective larvae

and after two weeks (and two molts) have developed into infective larvae

.

Ingestion of the copepods closes the cycle .

Ingestion of the copepods closes the cycle

CDC

DPDx Parasite

Image Library

|

| Figurre

14

Eggs of Toxocara canis. These eggs are passed in dog feces, especially puppies' feces. Humans do not produce or excrete eggs, and therefore eggs are not a diagnostic finding in human

toxocariasis! The egg to the left is fertilized but not yet embryonated, while the egg to the right contains a well developed larva. The latter egg would be infective if ingested by a human (frequently, a child).

Eggs of Toxocara canis. These eggs are passed in dog feces, especially puppies' feces. Humans do not produce or excrete eggs, and therefore eggs are not a diagnostic finding in human

toxocariasis! The egg to the left is fertilized but not yet embryonated, while the egg to the right contains a well developed larva. The latter egg would be infective if ingested by a human (frequently, a child).

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library

Toxocara canis (Dog Roundworm) egg, embryonated

Toxocara canis (Dog Roundworm) egg, embryonated

©

Dr Peter

Darben, Queensland University of Technology clinical parasitology

collection. Used with permission |

Toxocara canis

and T. catti (visceral larva migrans)

These are roundworms of dogs and cats

but they can infect humans and cause damage of the visceral organs. Eggs from

feces of infected animals are swallowed by man and hatch in the intestine. The

larvae penetrate the mucosa, enter the circulation and are carried to liver,

lungs, eyes and other organs where they cause inflammatory necrosis. Symptoms

are due to the inflammatory reaction at the site of infection. The most serious

consequence of infection may be loss of sight if the worm localizes in the eye. Treatment

includes Mebendazole to eliminate the worm and prednisone for inflammatory

symptoms. Avoidance of infected dogs and cats is the best prevention (figure 14

and 15).

|

Figure

15

Toxocara Life Cycle

Toxocara Life Cycle

Toxocara canis accomplishes its life cycle in dogs, with humans acquiring the infection as accidental hosts. Following ingestion by dogs, the infective eggs yield larvae that penetrate the gut wall and migrate into various tissues, where they encyst if the dog is older than 5 weeks. In younger dogs, the larvae migrate through the lungs, bronchial tree, and esophagus; adult worms develop and oviposit in the small intestine. In the older dogs, the encysted stages are reactivated during pregnancy, and infect by the transplacental and transmammary routes the puppies, in whose small intestine adult worms become established. Thus, infective eggs are excreted by lactating bitches and puppies. Humans are paratenic hosts who become infected by ingesting infective eggs in contaminated soil. After ingestion, the eggs yield larvae that penetrate the intestinal wall and are carried by the circulation to a wide variety of tissues (liver, heart, lungs, brain, muscle, eyes). While the larvae do not undergo any further development in these sites, they can cause severe local reactions that are the basis of

toxocariasis.

CDC

|

Figure

16

Ancylostoma brasiliense adult male and female

Ancylostoma brasiliense adult male and female

©

Dr Peter

Darben, Queensland University of Technology clinical parasitology

collection. Used with permission |

Ancylostoma

braziliensis (cutaneous

larva migrans, creeping eruption)

Creeping eruption is prevalent in many

tropical and subtropical countries and in the US especially along the Gulf and

southern Atlantic states. The organism is primarily a hookworm of dogs and cats

but the filariform larvae in animal feces can infect man and cause skin

eruptions. Since the larvae have a tendency to move around, the eruption

migrates in the skin around the site of infection. The symptoms last the

duration of larval persistence which ranges from 2 to 10 weeks. Light infection can

be treated by freezing the involved area. Heavier infections are treated with

Mebendazole. Infection can be avoided by keeping away from water and soil

contaminated with infected feces (figure 16 and 17).

|

A

B

Hookworm eggs examined on wet mount (eggs of Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus cannot be distinguished morphologically).

Diagnostic characteristics:

Size 57-76 µm by 35-47 µm

Oval or ellipsoidal shape

Thin shell

The embryo in B has begun cellular division and is at an early (gastrula) developmental stage.

CDC DPDx

Parasite Image Library |

Figure

17

Eggs are passed in the stool

Eggs are passed in the stool

,

and under favorable conditions (moisture, warmth, shade), larvae hatch

in 1 to 2 days. The released rhabditiform larvae grow in the feces

and/or the soil ,

and under favorable conditions (moisture, warmth, shade), larvae hatch

in 1 to 2 days. The released rhabditiform larvae grow in the feces

and/or the soil

, and after

5 to 10 days (and two molts) they become become filariform (third-stage)

larvae that are infective , and after

5 to 10 days (and two molts) they become become filariform (third-stage)

larvae that are infective

.

These infective larvae can survive 3 to 4 weeks in favorable

environmental conditions. On contact with the human host, the

larvae penetrate the skin and are carried through the veins to the heart

and then to the lungs. They penetrate into the pulmonary alveoli,

ascend the bronchial tree to the pharynx, and are swallowed .

These infective larvae can survive 3 to 4 weeks in favorable

environmental conditions. On contact with the human host, the

larvae penetrate the skin and are carried through the veins to the heart

and then to the lungs. They penetrate into the pulmonary alveoli,

ascend the bronchial tree to the pharynx, and are swallowed

.

The larvae reach the small intestine, where they reside and mature into

adults. Adult worms live in the lumen of the small intestine,

where they attach to the intestinal wall with resultant blood loss by

the host .

The larvae reach the small intestine, where they reside and mature into

adults. Adult worms live in the lumen of the small intestine,

where they attach to the intestinal wall with resultant blood loss by

the host

.

Most adult worms are eliminated in 1 to 2 years, but longevity records

can reach several years. .

Most adult worms are eliminated in 1 to 2 years, but longevity records

can reach several years.

Some A. duodenale larvae, following penetration of the host skin,

can become dormant (in the intestine or muscle). In addition,

infection by A. duodenale may probably also occur by the oral and

transmammary route. N. americanus, however, requires a

transpulmonary migration phase.

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library

|

| |

BLOOD AND TISSUE HELMINTHS

The major blood and tissue parasites

of man are microfilaria. These include Wuchereria bancrofti and W. (Brugia)

Malayi, Onchocerca volvulus, and Loa loa (eye worm).

|

|

|

Wuchereria bancrofti

and W. (Brugia) malayi (elephantiasis)

Epidemiology

W. bancrofti (figure 18) is strictly a human pathogen and is distributed in

tropical areas worldwide, whereas B. malayi (figure 19) infects a number of wild

and domestic animals and is restricted to South-East Asia. Mosquitoes are

vectors for both parasites.

Morphology

These two organisms are very similar in morphology and in the diseases they cause

(figure 18 and 19).

Adult female W. bancrofti found in lymph nodes and lymphatic channels are

10 cm x 250 micrometers whereas males are only half that size. Microfilaria found in

blood are only 260 micrometers x 10 micrometers. Adult B. malayi are only half

the size of W. bancrofti but their microfilaria are only slightly smaller than

W. bancrofti.

Life cycle

Filariform larvae enter the human body during a mosquito bite and migrate to

various tissues. There, they may take up to a year to mature and produce microfilaria

which migrate to lymphatics (figure 19) and, at night, enter the blood circulation.

Mosquitos are infected during a blood meal. The microfilaria

grow 4 to 5 fold in the mosquito in 10 to 14 days and become infective for man.

Symptoms

Symptoms include lymphadenitis and recurrent high fever every 8 to 10 weeks, which

lasts 3 to 7 days. There is progressive lymphadenitis due to an inflammatory

response to the parasite lodged in the lymphatic channels and tissues. As the

worm dies, the reaction continues and produces a fibro-proliferative granuloma

which obstructs lymph channels and causes lymphedema and elephantiasis (figure

20). The

stretched skin is susceptible to traumatic injury and infections. Microfilaria

cause eosinophilia and some splenomegaly. Not all infections lead to

elephantiasis. Prognosis, in the absence of elephantiasis, is good.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on history of mosquito bites in endemic areas, clinical

findings and presence of microfilaria in blood samples collected at night.

Treatment and control

Diethylcarbamazine quickly kills the adults worms or sterilizes

the female. It is given 2 mg/kg orally for 14 days. Steroids help alleviate

inflammatory symptoms. Cooler climate reduces the inflammatory reaction.

|

| |

|

|

Figure 18A

Figure 18A

Different species of the following genera of mosquitoes are vectors of

W.

bancrofti filariasis depending on geographical distribution.

Among them are: Culex (C. annulirostris, C.

bitaeniorhynchus, C. quinquefasciatus, and C. pipiens);

Anopheles (A. arabinensis, A. bancroftii, A.

farauti, A. funestus, A. gambiae, A. koliensis,

A. melas, A. merus, A. punctulatus and A.

wellcomei); Aedes (A. aegypti, A. aquasalis, A.

bellator, A. cooki, A. darlingi, A. kochi, A.

polynesiensis, A. pseudoscutellaris, A. rotumae, A.

scapularis, and A. vigilax); Mansonia (M.

pseudotitillans, M. uniformis); Coquillettidia (C.

juxtamansonia). During a blood meal, an infected mosquito

introduces third-stage filarial larvae onto the skin of the human host,

where they penetrate into the bite wound

.

They develop in adults that commonly reside in the lymphatics .

They develop in adults that commonly reside in the lymphatics

.

The female worms measure 80 to 100 mm in length and 0.24 to 0.30 mm in

diameter, while the males measure about 40 mm by .1 mm. Adults

produce microfilariae measuring 244 to 296 μm by 7.5 to 10 μm,

which are sheathed and have nocturnal periodicity, except the South

Pacific microfilariae which have the absence of marked periodicity.

The microfilariae migrate into lymph and blood channels moving

actively through lymph and blood .

The female worms measure 80 to 100 mm in length and 0.24 to 0.30 mm in

diameter, while the males measure about 40 mm by .1 mm. Adults

produce microfilariae measuring 244 to 296 μm by 7.5 to 10 μm,

which are sheathed and have nocturnal periodicity, except the South

Pacific microfilariae which have the absence of marked periodicity.

The microfilariae migrate into lymph and blood channels moving

actively through lymph and blood

.

A mosquito ingests the microfilariae during a blood meal .

A mosquito ingests the microfilariae during a blood meal

.

After ingestion, the microfilariae lose their sheaths and some of them

work their way through the wall of the proventriculus and cardiac

portion of the mosquito's midgut and reach the thoracic muscles .

After ingestion, the microfilariae lose their sheaths and some of them

work their way through the wall of the proventriculus and cardiac

portion of the mosquito's midgut and reach the thoracic muscles

.

There the microfilariae develop into first-stage larvae .

There the microfilariae develop into first-stage larvae

and subsequently into third-stage infective larvae

and subsequently into third-stage infective larvae

.

The third-stage infective larvae migrate through the hemocoel to the

mosquito's prosbocis .

The third-stage infective larvae migrate through the hemocoel to the

mosquito's prosbocis

and

can infect another human when the mosquito takes a blood meal and

can infect another human when the mosquito takes a blood meal

. .

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library

Figure 18B

Figure 18B

Microfilaria of Wuchereria bancrofti, from a patient seen in Haiti. Thick blood smears stained with

hematoxylin. The microfilaria is sheathed, its body is gently curved, and the tail is tapered to a point. The nuclear column (the cells that constitute the body of

themicrofilaria) is loosely packed, the cells can be visualized individually and do not extend to the tip of the tail. The sheath is

slightly stained with hematoxylin.

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library  Figure 18C

Figure 18C

Microfilaria of Wuchereria bancrofti collected by filtration with a

nucleopore membrane. Giemsa stain, which does not demonstrate the sheath of this sheathed species

(hematoxylin stain will stain the sheath lightly). The pores of the membrane are visible.

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library  Figure 19A

Figure 19A

Microfilaria of Brugia malayi. Thick blood smear, hematoxylin stain. Like Wuchereria

bancrofti, this species has a sheath (slightly stained in hematoxylin). Differently from

Wuchereria, the microfilariae in this species are more tightly coiled, and the nuclear column is more tightly packed, preventing the visualization of individual cells.

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library

Figure 19B

Figure 19B

Detail from the microfilaria of Brugia malayi

showing the tapered tail, with a subterminal and a terminal nuclei (seen as swellings at the level of the arrows), separated by a gap without nuclei. This is characteristic of B.

malayi.

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library

Figure 19C

Figure 19C

Wuchereria bancrofti adults in section of lymph node (H&E)

©

Dr Peter

Darben, Queensland University of Technology clinical parasitology

collection. Used with permission

Figure 19D

Figure 19D

Wuchereria bancrofti microfilaria in peripheral blood, giemsa stain

©

Dr Peter

Darben, Queensland University of Technology clinical parasitology

collection. Used with permission

Figure 19E

Figure 19E

The typical vector for

Brugia malayi filariasis are mosquito

species from the genera Mansonia and Aedes. During a

blood meal, an infected mosquito introduces third-stage filarial larvae

onto the skin of the human host, where they penetrate into the bite

wound  . They develop

into adults that commonly reside in the lymphatics . They develop

into adults that commonly reside in the lymphatics

.

The adult worms resemble those of Wuchereria bancrofti but are

smaller. Female worms measure 43 to 55 mm in length by 130 to 170

μm in width, and males measure 13 to 23 mm in length by 70 to 80

μm in width. Adults produce microfilariae, measuring 177 to

230 μm in length and 5 to 7 μm in width, which are sheathed

and have nocturnal periodicity. The microfilariae migrate into

lymph and enter the blood stream reaching the peripheral blood .

The adult worms resemble those of Wuchereria bancrofti but are

smaller. Female worms measure 43 to 55 mm in length by 130 to 170

μm in width, and males measure 13 to 23 mm in length by 70 to 80

μm in width. Adults produce microfilariae, measuring 177 to

230 μm in length and 5 to 7 μm in width, which are sheathed

and have nocturnal periodicity. The microfilariae migrate into

lymph and enter the blood stream reaching the peripheral blood

.

A mosquito ingests the microfilariae during a blood meal .

A mosquito ingests the microfilariae during a blood meal

.

After ingestion, the microfilariae lose their sheaths and work their way

through the wall of the proventriculus and cardiac portion of the midgut

to reach the thoracic muscles .

After ingestion, the microfilariae lose their sheaths and work their way

through the wall of the proventriculus and cardiac portion of the midgut

to reach the thoracic muscles

.

There the microfilariae develop into first-stage larvae .

There the microfilariae develop into first-stage larvae

and subsequently into third-stage larvae

and subsequently into third-stage larvae

.

The third-stage larvae migrate through the hemocoel to the mosquito's

prosbocis .

The third-stage larvae migrate through the hemocoel to the mosquito's

prosbocis

and can infect

another human when the mosquito takes a blood meal and can infect

another human when the mosquito takes a blood meal

. .

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library

Figure 20A

Figure 20A

Scrotal lymphangitis due to filariasis

CDC

Figure

20B Figure

20B

Inguinal lymph nodes enlarged due to filariasis.

CDC

Figure 20C

Figure 20C

Histopathology showing cross section of Dirofilaria worm in

eye.

CDC

Figure 20D

Figure 20D

An elderly village chief undresses prior to bathing. He has elephantiasis of the left leg, large hydrocoele, leopard skin and onchocerciasis nodules, one clearly visible on his

torso.

WHO/TDR/Crump

Figure 20 F

Figure 20 F

An elderly village chief sits bathing

himself outside his home with water from a bowl. He has elephantiasis of the left leg, large

hydrocoele, leopard skin on the left leg and onchocerciasis nodules.

WHO/TDR/Crump

Figure 20G

Figure 20G

An elderly village chief sits bathing

himself outside his home with water from a bowl. He has elephantiasis of the left leg, large

hydrocoele, leopard skin on the left leg and onchocerciasis nodules.

WHO/TDR/Crump

Figure 20H

Figure 20H

An elderly male with hydrocoele,

elephantiasis of the leg, hanging groin, leopard skin and onchocerciasis nodules.

WHO/TDR/Crump

Figure 20I

Figure 20I

An elderly male with hydrocoele,

elephantiasis of the leg, hanging groin and leopard skin.

WHO/TDR/Crump

Figure 20J

Figure 20J

The feet of a male villager showing elephantiasis and skin lesions of the

left leg and foot.

WHO/TDR/Crump

Figure 20K

Figure 20K

This lady has elephantiasis of the right leg and oedema in the left.

WHO/TDR/Crump

Figure

20L

Figure

20L

Elephantiasis of leg due to filariasis. Luzon, Philippines.

CDC

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

Figure 20E

Figure 20E

An elderly village chief undresses prior to bathing. He has

elephantiasis of the left leg, large hydrocoele, leopard skin and onchocerciasis nodules clearly visible on his torso.

WHO/TDR/Crump |

| |

|

|

Onchocerca volvulus

(Blinding filariasis; river blindness)

Epidemiology

Onchocerciasis is prevalent throughout eastern, central and

western Africa, where it is the major cause of blindness. In the Americas, it is

found in Guatemala, Mexico, Colombia and Venezuela. The disease is confined to

neighborhoods of low elevation with rapidly flowing small streams where black

flies breed. Man is the only host.

Morphology

Adult female onchocerca measure 50 cm by 300 micrometers, male worms are much

smaller. Infective larvae of O. volvulus are 500 micrometers by 25 micrometers

(figure 21).

Life cycle

Infective larvae are injected into human skin by the female black fly (Simulium

damnosum) where they develop into adult worms in 8 to 10 months. The adults

usually occur as group of tightly coiled worms (2 to 3 females and 1 to 2 males).

The gravid female releases microfilarial larvae, which are usually distributed

in the skin. They are picked up by the black fly during a blood meal. The larvae

migrate from the gut of the black fly to the thoracic muscle where they develop

into infective larvae in 6 to 8 days. These larvae migrate to the head of the fly

and then are transmitted to a second host.

Symptoms

Onchocerciasis results in nodular and erythematous lesions in the skin and

subcutaneous tissue due to a chronic inflammatory response to persistent worm

infection. During the incubation period of 10 to 12 months, there is eosinophilia

and urticaria. Ocular involvement consists of trapping of microfilaria in the cornea, choroid, iris and anterior chambers, leading to photophobia, lacrimation

and blindness (figure 21).

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on symptoms, history of exposure to black flies and presence

of microfilaria in nodules.

Treatment and control

Ivermectin is effective in killing the larvae, but does not affect the adult

worm. Preventive measures include vector control, treatment of infected

individuals and avoidance of black fly.

|

| |

|

Figure

21

|

Figure 21A

Figure 21A

Microfilaria of Onchocerca volvulus, from skin snip from a patient seen in Guatemala. Wet preparation. Some important

characteristics of the microfilariae of this species are shown here: no sheath present;

the tail is tapered and is sharply angled at the

end.

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library

Figure 21B

Figure 21B

Onchocerca volvulus.

CDC/Dr. Lee Moore

Figure 21C

Figure 21C

Onchocerca volvulus, posterior end.

CDC/Dr. Lee Moore

Figure 21D

Figure 21D

Face of a blind male patient in the onchocerciasis

ward.

WHO/TDR/Crump

Figure 21E

Figure 21E

Onchocerca volvulus adults in section of tumour (H&E)

©

Dr Peter

Darben, Queensland University of Technology clinical parasitology

collection. Used with permission

Figure 21F

Figure 21F

Histopathology of

Onchocerca volvulus nodule.

Onchocerciasis.

CDC/Dr. Mae Melvin

Figure 21G

Figure 21G

An old man, blinded by

onchocerciasis.

WHO/TDR/Crump

Figure 21H

Figure 21H

Life cycle of

Onchocerca volvulus

During a blood

meal, an infected blackfly (genus Simulium) introduces

third-stage filarial larvae onto the skin of the human host, where they

penetrate into the bite wound

.

In subcutaneous tissues the larvae .

In subcutaneous tissues the larvae

develop into adult filariae, which commonly reside in nodules in

subcutaneous connective tissues

develop into adult filariae, which commonly reside in nodules in

subcutaneous connective tissues

.

Adults can live in the nodules for approximately 15 years. Some

nodules may contain numerous male and female worms. Females

measure 33 to 50 cm in length and 270 to 400 μm in diameter, while

males measure 19 to 42 mm by 130 to 210 μm. In the

subcutaneous nodules, the female worms are capable of producing

microfilariae for approximately 9 years. The microfilariae,

measuring 220 to 360 µm by 5 to 9 µm and unsheathed, have a life span

that may reach 2 years. They are occasionally found in

peripheral blood, urine, and sputum but are typically found in the skin

and in the lymphatics of connective tissues .

Adults can live in the nodules for approximately 15 years. Some

nodules may contain numerous male and female worms. Females

measure 33 to 50 cm in length and 270 to 400 μm in diameter, while

males measure 19 to 42 mm by 130 to 210 μm. In the

subcutaneous nodules, the female worms are capable of producing

microfilariae for approximately 9 years. The microfilariae,

measuring 220 to 360 µm by 5 to 9 µm and unsheathed, have a life span

that may reach 2 years. They are occasionally found in

peripheral blood, urine, and sputum but are typically found in the skin

and in the lymphatics of connective tissues

.

A blackfly ingests the microfilariae during a blood meal .

A blackfly ingests the microfilariae during a blood meal

.

After ingestion, the microfilariae migrate from the blackfly's midgut

through the hemocoel to the thoracic muscles .

After ingestion, the microfilariae migrate from the blackfly's midgut

through the hemocoel to the thoracic muscles

.

There the microfilariae develop into first-stage larvae .

There the microfilariae develop into first-stage larvae

and subsequently into third-stage infective larvae

and subsequently into third-stage infective larvae

.

The third-stage infective larvae migrate to the blackfly's proboscis .

The third-stage infective larvae migrate to the blackfly's proboscis

and can infect another human when the fly takes a blood meal

and can infect another human when the fly takes a blood meal

. .

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library

|

| |

| |

Loa loa

(eye worm)

Loasis is limited to the areas of

African equatorial rain forest. The incidence in endemic areas varies greatly (8

to 75 percent). The larger, female organisms are 60 mm by 500 micrometers; males are

35mm by 300 micrometers in size (figure 22). The circulating microfilaria are 300

micrometers by 7 micrometers; the infective larvae in the fly are 200 micrometers

by 30 micrometers. The life

cycle of Loa loa (figure 23) is identical to that of onchocerca except that the vector for

this worm is the deer fly. The infection results in subcutaneous (Calabar)

swelling, measuring 5 to 10 cm in diameter, marked by erythema and

angioedema,

usually in the extremities. The organism migrates under the skin at a rate of up

to an inch every two minutes. Consequently, the swelling appears spontaneously,

persists for 4 to 7 days and disappears, and is known as fugitive or Calabar

swelling. The worm usually causes no serious problems, except when passing

through the orbital conjunctiva or the nose bridge. The diagnosis is based on

symptoms, history of deer fly bite and presence of eosinophilia. Recovery of

worms from the conjunctiva is confirmatory. Treatment and control are

achieved with diethylcarbamazine..

|

| |

Figure 22A

Figure 22A

Loa loa, posterior end.

CDC/Dr. Lee Moore

Figure 22B

Figure 22B

Loa loa, agent of filariasis. Anterior end.

CDC/Dr. Lee Moore

Figure 22C

Figure 22C

Microfilariae of Loa loa (right) and Mansonella perstans (left). Patient seen in Cameroon. Thick blood smear stained with

hematoxylin. Loa loa is sheathed, with a relatively dense nuclear column; its tail tapers and is frequently coiled, and nuclei extend to

the end of the tail. Mansonella perstans is smaller, has no sheath, and has a blunt tail with nuclei extending to the end of the tail.

CDC

Figure 23

Figure 23

The vector for

Loa loa filariasis are flies from two species of

the genus Chrysops, C. silacea and C. dimidiata.

During a blood meal, an infected fly (genus Chrysops, day-biting

flies) introduces third-stage filarial larvae onto the skin of the human

host, where they penetrate into the bite wound

.

The larvae develop into adults that commonly reside in subcutaneous

tissue .

The larvae develop into adults that commonly reside in subcutaneous

tissue

. The female

worms measure 40 to 70 mm in length and 0.5 mm in diameter, while the

males measure 30 to 34 mm in length and 0.35 to 0.43 mm in diameter.

Adults produce microfilariae measuring 250 to 300 μm by 6 to 8

μm, which are sheathed and have diurnal periodicity.

Microfilariae have been recovered from spinal fluids, urine, and sputum.

During the day they are found in peripheral blood, but during the

noncirculation phase, they are found in the lungs . The female

worms measure 40 to 70 mm in length and 0.5 mm in diameter, while the

males measure 30 to 34 mm in length and 0.35 to 0.43 mm in diameter.

Adults produce microfilariae measuring 250 to 300 μm by 6 to 8

μm, which are sheathed and have diurnal periodicity.

Microfilariae have been recovered from spinal fluids, urine, and sputum.

During the day they are found in peripheral blood, but during the

noncirculation phase, they are found in the lungs

.

The fly ingests microfilariae during a blood meal .

The fly ingests microfilariae during a blood meal

.

After ingestion, the microfilariae lose their sheaths and migrate from

the fly's midgut through the hemocoel to the thoracic muscles of the

arthropod .

After ingestion, the microfilariae lose their sheaths and migrate from

the fly's midgut through the hemocoel to the thoracic muscles of the

arthropod

. There the

microfilariae develop into first-stage larvae . There the

microfilariae develop into first-stage larvae

and

subsequently into third-stage infective larvae and

subsequently into third-stage infective larvae

.

The third-stage infective larvae migrate to the fly's proboscis .

The third-stage infective larvae migrate to the fly's proboscis

and can infect another human when the fly takes a blood meal

and can infect another human when the fly takes a blood meal

. .

CDC

DPDx

Parasite Image Library

|

| |

| |

|

Summary |

|

Organism |

Transmission |

Symptoms |

Diagnosis |

Treatment |

|

Ascaris lumbricoides

|

Oro-fecal |

Abdominal pain, weight

loss, distended abdomen

|

Stool: corticoid oval

egg (40-70x35-50 μm) |

Mebendazole |

|

Trichinella spiralis

|

Poorly cooked pork |

Depends on worm

location and burden: gastroenteritis; edema, muscle pain, spasm;

eosinophilia, tachycardia, fever, chill headache, vertigo, delirium, coma,

etc. |

Medical history, eosinophilia, muscle biopsy, serology |

corticosteroid and Mebendazole

|

|

Trichuris trichiura

|

Oro-fecal |

Abdominal pain, bloody

diarrhea, prolapsed rectum |

Stool: lemon-shaped egg

(50-55 x 20-25μm) |

Mebendazole |

|

Enterobius vermicularis

|

Oro-fecal |

Peri-anal pruritus,

rare abdominal pain, nausea vomiting |

Stool: embryonated eggs

(60x27 μm), flat on one side |

Pyrental pamoate or

Mebendazole

|

|

Strongyloides

stercoralis

|

Soil-skin,

autoinfection |

Itching at infection

site, rash due to larval migration, verminous pneumonia, mid-epigastric

pain, nausea, vomiting, bloody dysentery, weight loss and anemia |

Stool: rhabditiform

larvae (250x 20-25μm) |

Ivermectin or Thiabendazole

|

|

Necator americanes;

Ancylostoma duodenale

(Hookworms)

|

Oro-fecal (egg); skin

penetration (larvae) |

Maculopapular erythema

(ground itch), broncho-pneumonitis, epigastric pain, GI hemorrhage,

anemia, edema

|

Stool: oval segmented

eggs (60 x 30 20-25μm) |

Mebendazole |

|

Dracunculus medinensis

|

Oral: cyclops in water |

Blistering skin,

irritation, inflammation |

Physical examination |

Mebendazole

|

|

Wuchereria bancrofti;

W. brugia malayi

(elephantiasis)

|

Mosquito bite |

Recurrent fever, lymph-adenitis,

splenomegaly, lymphedema, elephantiasis |

Medical history,

physical examination, microfilaria in blood (night sample) |

Mebendazole; Diethyl-carbamazine |

|

Onchocerca volvulus |

Black fly bite |

Nodular and

erythematous dermal lesions, eosinophilia, urticaria, blindness |

Medical history,

physical examination, microfilaria in nodular aspirate |

Mebendazole; Diethyl-carbamazine |

|

Loa loa |

Deer fly |

As in onchocerciasis |

As in onchocerciasis |

Diethyl-carbamazine |

|

|

Return to the Parasitology Section of Microbiology and Immunology On-line

Return to the Parasitology Section of Microbiology and Immunology On-line

This page last changed on

Saturday, April 15, 2017

Page maintained by

Richard Hunt

|

Eggs, unfertilized (left) and fertilized (right). Patient seen in Haiti.

Eggs, unfertilized (left) and fertilized (right). Patient seen in Haiti.

Egg containing a larva, which will be infective if ingested. Patient seen in

Léogane, Haiti.

Egg containing a larva, which will be infective if ingested. Patient seen in

Léogane, Haiti.  Ancylostoma brasiliense adult male and female

Ancylostoma brasiliense adult male and female

Figure 20E

Figure 20E