|

x |

x |

|

|

|

|

INFECTIOUS

DISEASE |

BACTERIOLOGY |

IMMUNOLOGY |

MYCOLOGY |

PARASITOLOGY |

VIROLOGY |

|

SHQIP - ALBANIAN |

BACTERIOLOGY - CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

ZOONOSES

LISTERIA, FRANCISELLA,

BRUCELLA, BACILLUS, YERSINIA AND ERYSIPELOTHRIX

Dr Abdul Ghaffar

Professor Emeritus

University of South Carolina School of Medicine

|

|

EN ESPANOL - SPANISH |

|

Let us know what you think

FEEDBACK |

|

SEARCH |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Logo image © Jeffrey

Nelson, Rush University, Chicago, Illinois and

The MicrobeLibrary |

|

|

|

Arnold Boecklin:

The Plague 1898. Tempera on wood, Kunstmuseum, Basel

Arnold Boecklin:

The Plague 1898. Tempera on wood, Kunstmuseum, Basel |

|

TEACHING

OBJECTIVES

To know the general morphology

and physiology the organisms

To know epidemiology and clinical

symptoms

To understand the mechanisms

pathogenesis

To know the diagnostic, therapeutic

and preventive procedures

|

Zoonosis

refers to a disease primarily of animals which can be transmitted to humans as a

result of direct or indirect contact with infected animal populations.

BRUCELLOSIS

Morphology and physiology

Brucella are Gram-negative, non-motile, coccobacilli. They

are strict aerobes and grow very slowly (fastidious) on blood agar. In

the host, they live as facultative intracellular pathogens.

Epidemiology

Brucellosis is primarily a

disease of animals and it affects organs rich in the sugar

erythritol (breast,

uterus, epididymis, etc.). The organisms localize in these animal organs and

cause infertility, sterility,

mastitis, abortion.

They may also be carried asymptomatically. Humans

in close contact with infected animals (slaughterhouse workers, veterinarians,

farmers, dairy workers) are at risk of developing undulant fever. There

are 100 to 200 cases of brucellosis seen in the United States annually, although the worldwide

incidence is estimated at 500,000. Species of Brucella that are

known to infect humans include:

There are other species of Brucella that infect many

animals from whales to rats

Although brucellosis

has largely been eradicated in most developed countries through animal vaccination, it

persists in many underdeveloped and developing countries.

Ares where there is a higher risk of Brucella

infection include:

|

|

|

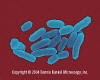

Brucella abortus - Gram-negative, coccobacillus prokaryote; causes bovine spontaneous abortion due to its rapid growth in the presence of

erythritol (produced in the plancenta). SEM x 29,650

©

Dennis Kunkel Microscopy, Inc.

Used with permission

Brucella abortus - Gram-negative, coccobacillus prokaryote; causes bovine spontaneous abortion due to its rapid growth in the presence of

erythritol (produced in the plancenta). SEM x 29,650

©

Dennis Kunkel Microscopy, Inc.

Used with permission

Brucella spp. are poorly staining, small gram-negative coccobacilli (0.5-0.7 x 0.6-1.5

micrometer), and are seen mostly as single cells and appearing like “fine sand”

CDC

Brucella spp. are poorly staining, small gram-negative coccobacilli (0.5-0.7 x 0.6-1.5

micrometer), and are seen mostly as single cells and appearing like “fine sand”

CDC

Brucella spp. Colony Characteristics: A. Fastidious, usually not visible at 24h. B. Grows slowly on most standard laboratory media (e.g. sheep blood, chocolate and trypticase soy agars). Pinpoint, smooth, entire translucent,

Brucella spp. Colony Characteristics: A. Fastidious, usually not visible at 24h. B. Grows slowly on most standard laboratory media (e.g. sheep blood, chocolate and trypticase soy agars). Pinpoint, smooth, entire translucent,

non-hemolytic at 48h.

CDC

Brucella ovis in

epididymis © Bristol Biomedical Image Archive, University of

Bristol. Used with permission

Brucella ovis in

epididymis © Bristol Biomedical Image Archive, University of

Bristol. Used with permission |

Transmission

Infection

may occur by:

-

Direct contact with infected

animals or animal products

-

Ingestion of animal products

such as unpasteurized milk, milk products (including cheeses),

undercooked meat. This is probably the most frequent cause of human

Brucella infections and are of particularly important for tourists

-

Breathing in bacteria/ This may occur in people in

contact with infected animals or in laboratories where Brucella

is handled.

-

Entry through wounds or mucous membranes. In addition,

to those mentioned above, this may occur in hunters. Infected game

animals may include (CDC): Bison, elk, caribou, moose, feral hogs.

-

Breast feeding. Person to person transmission is very

rare but has been reported

-

Sexual activity. Again this is very rare

-

Possibly in tissue transplantation or organ transplant.

Again, this is very rare.

CDC notes that it is especially important that expectant

mothers who have been exposed to Brucella should consult a physician

as post-exposure prophylaxis may be required.

The bacteria are engulfed by neutrophils and

monocytes and localize in the regional lymph nodes, where they proliferate

intracellularly. If the Brucella organisms are not destroyed or contained in the

lymph nodes, the bacteria are released from the lymph nodes resulting in

septicemia. The organisms migrate to other lympho-reticular organs (spleen, bone

marrow, liver, testes) producing granulomas and/or micro abscesses.

Symptoms

B. abortus

and B. canis cause a mild suppurative febrile infection whereas B.

suis causes a more severe

suppurative infection which can lead to

destruction of the lymphoreticular organs and kidney. B. melitensis is

the cause of most severe prolonged recurring disease. The bacteria enter the

human host through the mucous membranes of the oropharynx (ingestion/inhalation

routes), through abraded skin, or through the conjunctiva.

Symptoms

include:

Brucellosis may be either acute or

chronic.

Mortality due to Brucellosis is

rare (less than 3%) and is generally due to endocarditis.

Pathogenesis

The symptoms of brucellosis are due to the presence of the organism and appear

2 to 4 weeks (sometimes up to 2 months) after exposure. While in the phago-lysosome,

B. abortus releases 5'-guanosine and adenine which are capable of

inhibiting the degranulation of peroxidase-containing granules and thus inhibit

the myeloperoxidase-peroxide-halide system of bacterial killing. The

intracellular persistence of bacteria results in granuloma formation in the

reticuloendothelial system organs and tissue damage due to hypersensitivity

reactions, mostly type-IV.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on prolonged (at least a week) presence of undulating fever,

myalgia,

arthralgia and the history of exposure (contact with animals or

consumption of unprocessed material from infected animals). Definitive diagnosis

can be made by culturing blood samples on blood enriched media. The (fastidious)

organisms grow very slowly (4 to 6 weeks in blood culture). B. abortus but

not other Brucella grow better in 5% CO2 atmosphere. On blood

agar, they produce white glistening colonies. Serology can be used to further

confirm the diagnosis.

Prevention and treatment

Prolonged (6 to 8 weeks) treatment with rifampin

or doxycycline along with streptomycin or tetracyclin is used to treat human Brucella infections.

Control

measures include animal vaccination and avoidance of infected material.

|

|

|

|

Dr. Alexandre Yersin in Front of the National Quarantine Station, Shanghai

Station, 1936

Dr. Alexandre Yersin in Front of the National Quarantine Station, Shanghai

Station, 1936

World distribution of plague 1998

CDC

World distribution of plague 1998

CDC

World distribution of plague 2000-2009

CDC

US distribution of plague by county

1970-2012

CDC

Cases of plague in the United States by year. 1970-2012

CDC

Yersinia pestis - rod prokaryote (dividing); causes bubonic plague (SEM x20,800)

©

Dennis Kunkel Microscopy, Inc.

Used with permission

Yersinia pestis - rod prokaryote (dividing); causes bubonic plague (SEM x20,800)

©

Dennis Kunkel Microscopy, Inc.

Used with permission

Yersinia pestis. Fluorescent antibody

identification CDC Yersinia pestis. Fluorescent antibody

identification CDC

|

PLAGUE

Plague is caused by Yersinia

pestis and is the disease known in the middle ages as the black death.

This is because it frequently leads to gangrene and blackening of various

parts of the body. Capillary fragility results in hemorrhages in the skin

which also result in black patches.

Morphology and physiology

Yersinia pestis is a

pleomorphic, Gram-negative, bipolar staining,

facultatively aerobic, non-motile bacillus. Optimal temperature for growth is 28

degrees C. It is a facultative intracellular parasite.

Epidemiology, transmission and

symptoms

The three documented pandemics of

plague (Black Death) have been responsible for the death of hundreds of millions

of people. Today, sporadic infections still occur. In the U.S., animal (sylvatic)

plague occurs in a number of western states, usually in small rodents and in

carnivores which feed on these rodents. The last urban outbreak of plague

occurred in the United States in 1924-25. There was an outbreak of

plague in India in 1994. In both cases, rats were the vector.

Sporadic plague still occurs in the rural United States.

Infected animals include:

-

squirrels (rock and ground)

-

wood rates

-

prairie dogs

-

mice

-

chipmunks

-

voles

-

rabbits

-

also carnivores may be infected by eating infected

prey. In the United States, pneumonic plague has occurred in recent

years from contact with infected cats that have been infected after

eating infected rodents.

Humans are usually infected by carrier

rodent fleas. The flea acquires the Y.

pestis organisms during a blood meal from infected rodents. The bacteria

lose their capsule, multiply in the intestinal tract and partially block the proventriculus.

When the flea feeds on a human host, it may regurgitate some of

the organisms into the wound.

Humans can also can be infected in other ways such as by

contact with infected animals or handling carcasses of infected animals.

This usually results in bubonic or septicemic plague.

Plague can also be spread in aerosols in a cough or

sneeze from a person (or pet cat) with pneumonic plague.

The bulk of non-capsular organisms are phagocytized and destroyed by neutrophils. However,

a few organisms are taken up

by histiocytes which are unable to kill them and allow them to resynthesize

their capsule and multiply. The encapsulated organisms, when they are released

from histiocytes, are resistant to phagocytosis and killing by neutrophils. The

resulting infection spreads to the draining lymph nodes which become hot,

swollen, tender and hemorrhagic giving rise to the characteristic black buboes

whence the name of the disease, bubonic plague, is derived. Within

hours the organism spreads into the spleen, liver and lungs resulting in

pneumonia. While in the circulation, the organism causes diffuse intra-vascular

coagulation resulting in intra-vascular thrombi and purpuric lesions all over the

body. If untreated, the infection has a very high (up to 90%) mortality rate. The

organisms in exhaled in cough droplets, infect other humans in close proximity

and cause pneumonic plague, which is more difficult to control and has 100%

mortality.

Pathogenesis

Many factors play direct and indirect roles in

Y. pestis

pathogenesis.

Low calcium response (lcr)

This is a plasmid-coded gene that

enables the organism to grow in a low Ca++ (intracellular) environment. It

also coordinates the production of several other virulence factors, such as

V, W and yops (Yersinia outer proteins).

V and W proteins

These plasmid-coded proteins are associated rapid proliferation and

septicemia.

Yops

A group of 11 proteins, which are coded by plasmids, are essential for

rodent pathogenesis and are responsible for cytotoxicity, inhibition of

phagocyte migration and engulfment and platelet aggregation.

Envelope (F-1) antigen

This is a protein-polysaccharide complex which is highly expressed at 37

degrees in

the mammalian host but not in the flea and is anti-phagocytic.

Coagulase and Plasminogen

activator

Both of these are plasmid-coded proteins.

Coagulase is responsible for micro thrombi formation

and

plasminogen activator

promotes the dissemination of the organism. It

also destroys C3b on the bacterial surface, thus attenuating phagocytosis.

|

|

|

Plague suits. The beak was filled with sweet smelling oils and vinegar

to counteract the smell of plague victims. Although physicians in the 1300's

did not know the cause of plague, the suits may have been effective to some

degree in that they kept fleas off and the shiny beak may have posed an

obstacle to the entry of fleas. Left From:

Bubonic Plague by Ely Janis Right:

©

Bristol Biomedical Image Archive, University of Bristol. Used with

permission

Plague suits. The beak was filled with sweet smelling oils and vinegar

to counteract the smell of plague victims. Although physicians in the 1300's

did not know the cause of plague, the suits may have been effective to some

degree in that they kept fleas off and the shiny beak may have posed an

obstacle to the entry of fleas. Left From:

Bubonic Plague by Ely Janis Right:

©

Bristol Biomedical Image Archive, University of Bristol. Used with

permission

|

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on appearance of buboes

(swollen lymph glands). The diagnosis is confirmed by

culture of a lymph node aspirate. Extreme caution is warranted in handling of

the specimen, as it is highly infectious. In cases of pneumonic and septicemic

plague there may be no obvious signs.

Prevention and Treatment

Hospitalization and strict isolation are the rule

for this serious but easily treatable disease.

Streptomycin and gentamycin

are highly effective but other effective antibiotics include tetracycline,

fluoroquinalones and chloramphenicol. For most recent CDC

recommendations go

here.

An effective formalin-killed vaccine is available but is

recommended only for people at a high risk. The disease is internationally quarantinable and reporting of cases is mandatory. Control of urban plague is

based upon flea and rodent control.

Summary of types and symptoms of plague

Bubonic plague

|

An

axillary bubo and edema exhibited by a plague patient

CDC/Margaret Parsons, Dr.

Karl F. Meyer |

This usually occurs as a result of a bite by an infected flea.

The lymph nodes closest to the bite become swollen as the bacteria

proliferate. They can then spread to other parts of the body.

Symptoms of bubonic plague Sudden onset of

- Fever

- Headache

- Weakness

- Formation of buboes (swollen, tender lymph nodes). See

below

Pneumonic plague

|

Anteroposterior chest x-ray of a

plague patient revealing bilateral infection,

greater on the patient's left side, which was

diagnosed as a case of pneumonic plague, caused

by the bacterium, Yersinia pestis.

CDC/ Dr. Jack

Poland |

This is usually the result of inhaling aerosols from an

infected patient or animal. It can also develop as the

result of spread of bacteria to the lungs in other forms of

plague that remain untreated. It is the most serious form of

plague as it can easily be spread.

Symptoms of pneumonic plague

- Fever

- Headache

- Weakness

- Pneumonia (chest pain, cough with sometimes

watery or bloody mucous, shortness of breath)

Septicemic plague

|

A 59 year-old man’s hands

who had been infected by the plague

bacterium, Yersinia pestis, after

having come into contact with both an

infected cat, and a dead mouse in his

neighborhood. The gangrenous condition

of the fingers had turned the dead

digits black, and mummified.

Two days after the

exposure the patient developed fever and

myalgias, and by the following day he

had developed a left axillary bubo.

Seven days after the initial exposure he

became critically ill and was admitted

to the hospital with multiple organ

failure. Initial blood cultures were

positive for double-curved,

Gram-negative Y. pestis rods.

The patient was

treated with gentamicin and survived,

but necrosis of the hands and feet

developed during hospitalization. He

subsequently required amputation of the

hands and feet.

CDC PHIL |

|

Swollen lymph glands (buboes) caused by plague bacteria in bubonic plague CDC |

This comes from flea bits or contact with an

infected animal. It may the initial disease or the

consequence of untreated bubonic plague.

Symptoms of septicemic plague

- Fever

- Chills

- Weakness

- Abdominal pain

- Shock

- Bleeding in skin and organs

- Skin, particularly at extremities,

becomes black and necrotic

|

|

|

Male Xenopsylla cheopsis (oriental rat flea) engorged with blood CDC Male Xenopsylla cheopsis (oriental rat flea) engorged with blood CDC

Wayson stain of

Yersinia pestis. Note the characteristic safety pin

appearance of bacteria CDC Wayson stain of

Yersinia pestis. Note the characteristic safety pin

appearance of bacteria CDC

Symptoms in this plague patient include an inguinal bubo CDC

Symptoms in this plague patient include an inguinal bubo CDC

Histopathology of spleen in fatal human plague - Necrosis and Yersinia

pestis. CDC/Dr. Marshall Fox

Histopathology of spleen in fatal human plague - Necrosis and Yersinia

pestis. CDC/Dr. Marshall Fox

Histopathology of lymph node in fatal human plague - Medullary necrosis with fluid and Yersinia

pestis. CDC/Dr. Marshall Fox

Histopathology of lymph node in fatal human plague - Medullary necrosis with fluid and Yersinia

pestis. CDC/Dr. Marshall Fox

Capillary fragility is one of the manifestations of a plague infection, evident here on the leg of an infected patient.

CDC

Capillary fragility is one of the manifestations of a plague infection, evident here on the leg of an infected patient.

CDC

Gangrene is one of the manifestations of plague, and is the origin of the term "Black Death" given to plague throughout the ages

CDC

Gangrene is one of the manifestations of plague, and is the origin of the term "Black Death" given to plague throughout the ages

CDC

Plague patient displying a swollen axillary lymph node CDC

Plague patient displying a swollen axillary lymph node CDC

Dark stained bipolar ends of Yersinia pestis can clearly be seen in

this Wright's stain of blood from a plague victim

Dark stained bipolar ends of Yersinia pestis can clearly be seen in

this Wright's stain of blood from a plague victim

Yersinia

pestis grows

well on most standard laboratory media, after 48-72 hours, grey-white to

slightly yellow opaque raised, irregular “fried egg” morphology;

alternatively colonies may have a “hammered copper” shiny

surface. CDC

Yersinia

pestis grows

well on most standard laboratory media, after 48-72 hours, grey-white to

slightly yellow opaque raised, irregular “fried egg” morphology;

alternatively colonies may have a “hammered copper” shiny

surface. CDC

|

|

|

|

|

Robert Koch's original micrographs of

anthrax bacillus DOD Anthrax Program

Robert Koch's original micrographs of

anthrax bacillus DOD Anthrax Program

Gram stain of anthrax DOD Anthrax Program

Gram stain of anthrax DOD Anthrax Program

|

ANTHRAX

Morphology and physiology

Bacillus anthracis is the causative agent of anthrax. It is a

Gram-positive, aerobic, spore-forming large bacillus. Spores are formed in

culture, in the soil, and in the tissues and exudates of dead animals, but not

in the blood or tissues of living animals. Spores remain viable in soil for

decades.

Epidemiology, transmission and

symptoms

Anthrax is a major disease threat

to herbivorous animals (cattle, sheep, and to a lesser extent horses, hogs, and

goats). People become infected by the cutaneous route (direct contact with

diseased animals, industrial work with hides, wool, brushes, or bone meal), by

inhalation (Woolsorter's disease), or by ingestion (meat from diseased

animals). It is not contagious.

|

|

Anthrax due to Bacillus anthracis

(blood smear) ©

Bristol Biomedical Image Archive, University of Bristol. Used with

permission

Anthrax due to Bacillus anthracis

(blood smear) ©

Bristol Biomedical Image Archive, University of Bristol. Used with

permission

Under a very high magnification of 31,207X, this scanning

electron micrograph (SEM) depicted spores from the Sterne strain of

Bacillus anthracis bacteria CDC/ Laura Rose/Janice Haney Carr

Cutaneous Anthrax DOD Anthrax Program

Cutaneous Anthrax DOD Anthrax Program

Cutaneous anthrax CDC Cutaneous anthrax CDC |

accounts

for more than 95% of human cases. Spores enter through small break in skin,

germinate into vegetative cells which rapidly proliferate at the portal of

entry. Within a few days, a small papule emerges that becomes vesicular. The

latter is filled with blue-black edema fluid. Rupture of this lesion will reveal

a black eschar

at the base surrounded by a zone of

induration.

This lesion is called a malignant pustule; however, no pus or pain are

manifested. The lesion is classically found on the hands, forearms or head. The

invasion of the bloodstream will lead to systemic dissemination of bacteria.

Pulmonary anthrax

results form inhalation of B. anthracis spores which are

phagocytized

by

the alveolar macrophages where they germinate and replicate. The injured host

cell and organisms infect the hilar lymph node where marked hemorrhagic

necrosis may occur. The patient may manifest fever, malaise, myalgia, and a

non-productive cough. Once in the hilar lymph node, infection may spread into the

blood stream. Respiratory distress and cyanosis are manifestations of toxemia.

Death results within 24 hours. This form of anthrax is of significance in biological warfare.

results from ingestion of meat-derived from an infected animal and leads to

bacterial proliferation within the gastrointestinal tract, invasion of the

epithelium and

ulceration of the mucosa. The invasion spreads to the mesenteric lymph nodes and

then to the bloodstream. Initially, there is vomiting and diarrhea followed by blood in

the feces. Invasion of the bloodstream is associated with profound prostration,

shock and death. Because of strict control measures, this form of anthrax is

not seen in the U.S. Without treatment of gastrointestinal anthrax, the majority

of patients die but with antibiotic treatment, 60% or more

survive.

Injection anthrax is are and has not been

seen in North America but has occurred in heroin users in

northern Europe. Symptoms are similar to cutaneous anthrax but

the infection may be deeper at the site of needle entry. The

bacteria can spread more rapidly from site of infection to other

parts of the body than is the case with cutaneous anthrax.

Meningeal Anthrax. All forms of anthrax

above can progress to meningeal encephalitis with deep brain

hemorrhagic lesions and infection of the cerebro-spinal fluid.

It is almost always fatal.

Summary of types and symptoms of anthrax

Cutaneous anthrax

Symptoms

-

Blisters near site of infection

-

After the blister, a painless ulcer appears with

a black center with swelling. This is most often on the face,

neck, arms or hands

|

Cutaneous anthrax lesion on the

volar surface of the right forearm CDC |

|

Development of cutaneous anthrax CDC |

Pulmonary anthrax

Symptoms

Gastrointestinal anthrax

Symptoms

-

Fever and chills

-

Headache

-

Neck swelling

-

Red face and eyes

-

Sore throat, hoarseness and pain swallowing

-

Nausea and bloody vomit

-

Stomach cramps and stomach swelling

-

Diarrhea,

sometimes bloody

-

Faintness

-

Malaise

Injection anthrax

Symptoms

-

Fever and chills

-

Small blisters at site of drug injection

-

A painless ulcer with a black center with

swelling at site of injection after blisters appear

-

Deep abscess at injection site

|

|

CASE REPORT

Inhalation Anthrax Case

in Pennsylvania - 2006 |

| |

Anthrax skin lesion on face of man CDC Anthrax skin lesion on face of man CDC

Anthrax skin lesion on neck of man CDC Anthrax skin lesion on neck of man CDC

Marked hemorrhage in mucosa and submucosa with arteriolar

Marked hemorrhage in mucosa and submucosa with arteriolar

degeneration.

CDC/Dr. Marshall Fox

Histopathology of liver in fatal human anthrax. Dilated sinusoids, neutrophil infiltrate.

CDC/Dr. Marshall Fox

Histopathology of liver in fatal human anthrax. Dilated sinusoids, neutrophil infiltrate.

CDC/Dr. Marshall Fox

53 year old

female, employed 10 years in the spinning department of a goat-hair

processing mill. Cutaneous anthrax lesion on right cheek; lesion as seen

on 4th day CDC

lesion as seen on 5th

day CDC

lesion as seen on

6th day CDC

lesion as seen on 8th

day CDC

lesion as seen on 11th

day CDC

lesion as seen on 13th

day CDC

|

| |

| |

|

|

Pathogenesis

The virulence factors of B. anthracis include a number of exotoxins and

the capsule.

Exotoxin

A

plasmid-encoded, heat-labile, heterogeneous protein complex made up of 3

components:

-

Edema Factor (EF)

-

Lethal Factor (LF)

-

Protective Antigen (PA).

In vivo, these three factors act

synergistically (for toxic effects). The protective antigen binds to surface

receptors on eucaryotic cells and is subsequently cleaved by a cellular

protease. The larger C-terminal piece of PA remains bound to the receptor and

then binds either EF or LF, which enters the cell by

endocytosis. Edema Factor,

when inside the cells binds calmodulin-dependent and acts as adenylate cyclase.

Lethal factor's mechanism of action involves activation of macrophages and

production of cytokines which cause necrosis, fever, shock and death.

Individually, the three proteins have no known toxic activity. Antibodies to

protective antigens prevent PA binding to cells stop EF and LF entry.

Capsule

The capsule consists of a polypeptide of D-glutamic acid which is encoded by a

plasmid and is anti-phagocytic. It is not a good

immunogen and, even if any

antibodies produced, they are not protective against the disease.

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis of anthrax can be confirmed by direct examination or culture.

Fresh smears of vesicular fluid, fluid from under the eschar, blood, or spleen

or lymph node aspirates are stained with polychrome methylene blue and examined

for the characteristic blunt ended, blue-black rods with a pink capsule. In case

of a negative finding, the specimen can be cultured on blood agar plates.

Cultured organisms stain as Gram-positive long thin rods.

Prevention and Treatment

Antibiotics

Penicillin and the 4-quinolone,

Ciprofloxacin (Cipro), are the antibiotics of choice.

Anti-toxin

Antibody to the toxin complex is

neutralizing and protective. This may be used in combination with antibiotics.

There are two vaccines available. One is for use

for immunizing cattle and other herbivorous animals and the other for at-risk humans

(certain laboratory workers, people who handle animals (veterinarians)

and some military personnel.

|

|

|

Mediastinal widening

and pleural effusion on chest X-ray in inhalational anthrax CDC

Mediastinal widening

and pleural effusion on chest X-ray in inhalational anthrax CDC

|

| |

Infection of

macrophages or parenchymal cells by Listeria monocytogenes

Infection of

macrophages or parenchymal cells by Listeria monocytogenes

Listeria monocytogenes - rod prokaryote that causes listeriosis, meningitis and food poisoning

©

Dennis Kunkel Microscopy, Inc.

Used with permission

Listeria monocytogenes - rod prokaryote that causes listeriosis, meningitis and food poisoning

©

Dennis Kunkel Microscopy, Inc.

Used with permission

Live sheep: listeriosis

© Bristol Biomedical Image Archive, University of Bristol. Used with permission

Listeria monocytogenes organisms in neutrophil

(blood smear) © Bristol Biomedical Image Archive,

University of Bristol. Used with permission

Listeria monocytogenes organisms in neutrophil

(blood smear) © Bristol Biomedical Image Archive,

University of Bristol. Used with permission

Electron micrograph of a flagellated Listeria monocytogenes bacterium, Magnified

41,250X

Electron micrograph of a flagellated Listeria monocytogenes bacterium, Magnified

41,250X

CDC/Dr. Balasubr Swaminathan; Peggy Hayes; Elizabeth White

Electron micrograph of a Listeria bacterium in tissue.

Electron micrograph of a Listeria bacterium in tissue.

CDC/Dr. Balasubr Swaminathan; Peggy Hayes;

Elizabeth White |

LISTERIOSIS

Listeriosis is serious disease which is almost always caused by eating

contaminated food. It most affects newborn children, older and

immunocompromized people and pregnant women. There are about 1,600 cases of

listeriosis annually in the United States and about 260 deaths. In 2013, the

incidence of listeriosis was 2.6 cases per million.

Morphology and Physiology

L.monocytogenes is a facultative intracellular, Gram-positive

coccobacillus which often grows in short chains. It is different from other

Gram-positive organisms in that it contains a molecule chemically and

biologically similar to the classical lipopolysaccharide, the listerial LPS. The

organism forms beta hemolytic colonies on blood agar plates and blue-green

translucent colonies on colorless solid media. Upon infecting a cell

(macrophages and parenchymal cells), the organism escapes from the host vacuole

(or phagosome) and undergoes rapid division in the cytoplasm of the host cell

before becoming encapsulated by short actin filaments. These filaments

reorganize into a long tail extending from only one end of the bacterium. The

tail mediates movement of the organism through the cytoplasm to the surface of

the host cell. At the cell periphery, protrusions are formed that can then

penetrate neighboring cells and allow the bacterium to enter. Due to this mode

of cell-cell transmission, the organisms are never extracellular and exposed to

humoral antibacterial agents (e.g., complement, antibody). L.

monocytogenes is readily killed by activated macrophage.

Epidemiology and symptoms

Listeria monocytogenes is

a ubiquitous organism found in the soil, vegetation, water, and in the

gastrointestinal tract of animals. Exposure to the organism can lead to

asymptomatic miscarriage or disease in humans. At greatest risk for the

disease are the fetus, neonates, cancer patients and immuno-compromised

persons. In the United States, a number of recent outbreaks have been traced to

cheese, cole slaw (cabbage), milk, and meat. The organisms can grow at 4

degrees C which means that organism replication continues in refrigerated foods.

Laboratory isolation can employ a cold enrichment technique.

Listeriosis has been categorized in

two forms: 1) neonatal disease and 2) adult disease.

Neonatal Disease

Neonatal disease can occur in two forms:

-

Early onset disease,

acquired transplacetally in utero

In utero acquired infection (granulomatosus

infantiseptica) causes abscesses and granulomas in multiple organs and very

frequently results in abortion.

-

Late onset disease

acquired at birth or soon after birth.

Exposure on vaginal delivery results in

the late onset disease resulting in meningitis or meningo-encephalitis with

sepsis within 2 to 3 weeks.

Adult Disease

Infection in normal adults results in self-resolving flu-like symptoms

and/or mild gastrointestinal disturbance. Chills and fever are due to bacteremia.

In pregnant women, infection can lead to miscarriage, still birth or

premature birth with life-threatening

In immunosuppressed individuals

listeriosis can produce serious illness,

leading to meningitis. It is one of the leading causes of bacterial

meningitis in patients with cancer and in renal transplant recipients. In

the elderly, the early symptoms may go unnoticed and the infection may lead

to acute manifestations of sepsis (high fever, hypo-tension). A complication

of the bacteremia is endocarditis.

Pathogenesis

Listeriolysin O, a β-hemolysin,

is related to streptolysin, and pneumolysin and is produced by virulent strains. It disrupts the phagocytic vacuole and is

instrumental in cell-cell transmission of the organism. The toxin is oxygen

labile and immunogenic.

Diagnosis

Listeriosis is indicated when blood and CSF monocytosis is observed. The

organism can be isolated on most laboratory media.

Treatment and control

Penicillin (ampicillin) alone or in combination with gentamycin have been

effective. Immunity is cell-mediated.

|

Thumb with skin ulcer of tularemia.

CDC/Emory U./Dr. Sellers

Thumb with skin ulcer of tularemia.

CDC/Emory U./Dr. Sellers

Tularemia lesion on the dorsal skin of right hand

CDC/Dr. Brachman

Tularemia lesion on the dorsal skin of right hand

CDC/Dr. Brachman

Tularemia on the hand CDC

Francisella tularensis bacteria stained with methylene blue CDC/Dr.

P. B. Smith

Francisella tularensis bacteria stained with methylene blue CDC/Dr.

P. B. Smith

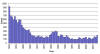

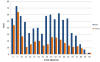

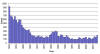

Reported cases of tularemia in the United States 1050-2010

CDC

Reported cases of tularemia in the United States 1050-2010

CDC

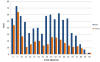

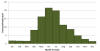

Average annual

incidence rate of tularemia by sex and age group - United States,

2001-2010 CDC

Average annual

incidence rate of tularemia by sex and age group - United States,

2001-2010 CDC

Reported tularemia cases in the United States - 2004 - 2013

CDC

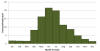

Reported cases of tularemia by month in the United States

2001-2010 CDC

|

TULAREMIA

Morphology and physiology

Francisella tularensis is a small, Gram-negative,

non-motile, encapsulated,

pleomorphic coccobacillus (short rod). It is a facultative intracellular

parasite which grows poorly or not at all on most laboratory media and requires a

special glucose cysteine blood agar for isolation. Care must be taken in

handling the sample because of the low infectious dose.

Epidemiology and symptoms

Francisella tularensis is the causative agent of tularemia (a reportable

disease in the U.S.). Unlike plague, tularemia occurs routinely in all 50 of the

United States. Its primary reservoirs are rabbits, hares, rodents and ticks.

People most

commonly acquire tularemia via insect bites (ticks primarily, but also deer

flies, mites, blackflies, or mosquitoes) or by handling infected animal tissues.

Human disease (rabbit or deer fly fever) is characterized by a focal ulcer at

the site of entry of the organisms and enlargement of the regional lymph nodes.

In 2013, there were 203 cases of tularemia in the United

States (incidence: 0.6 cases per million population). Because the disease is

spread by ticks and flies, it is most common in the summer months.

As few as10 - 50 bacilli will cause

disease in humans if inhaled or introduced intradermally, whereas a very large

inoculum (~108 organisms) is required for the oral route of

infection. Incubation period is 3 - 10 days. A small skin papule usually develops

at the site of entry. Ulceration occurs together with fever, chills, malaise,

fatigue, and usually lymphadenopathy. Bacteremia usually occurs and the bacilli

then grow intracellularly in the reticuloendothelial system. Dissemination of

the organisms through the bloodstream permits focal lesions to develop in

numerous organs. The patient will normally exhibit one of several clinical

syndromes and the infection can be life-threatening, although most cases are

mild.

Forms of tularemia

Ulceroglandular tularemia

This form is most common (70 - 85% of cases) in which a

painful ulcerating papule, which has a necrotic center and raised periphery,

develops at the site of infection (usually from a tick or fly bite). The patient

experiences a fever (which can be as high as 104 degrees F) together

with lymph node swelling particularly in the arm pit and groin.

Glandular tularemia

This is acquired in the same way as ulceroglandular tularemia; however,

there is lymphadenopathy but no ulcer.

Oculoglandular

tularemia

This is often acquired when a person handling infected meat rubs the

bacteria into the eye. There is inflammation of the eye and swelling of

regional lymph glands.

Pneumonic tularemia

This is a very serious disease that

comes from breathing in the bacteria in dust or aerosols. It results in

difficulty breathing, chest pain and cough. It can also result from not

treating other forms of tularemia resulting is dissemination to the

lungs.

Oropharyngeal

tularemia

In this form, the disease is acquired by eating or drinking contaminated

food or drink. Patients experience pharyngotoncillitis

with lymphadenopathy accompanied by mouth ulcers. This is a rare form of

tularemia.

Pathogenesis

The capsule of the organism renders it resistant to phagocytosis.

Intracellularly, the organisms resist killing by phagocytes and multiply. Most

of the symptoms are due to cell-mediate hypersensitivity.

Diagnosis

F. tularensis is difficult to visualize in direct smears. The organism

can be isolated from specimens of sputum, or lymph node aspirates inoculated on

chocolate blood agar. Blood cultures are often negative. The organism grows very

slowly and hence must be incubated for several days. The identity of the

organism is confirmed with specific antisera.

Prevention and treatment

Streptomycin is the drug of choice for all forms of tularemia. Untreated, cases

have a fatality rate of 5 - 15%. A live attenuated organism vaccine is available

but its use is restricted to those persons who are at risk. Immunity appears to

be cell mediated. One must avoid handling infected animals, watch out for ticks

and utilize clean water supplies.

|

|

WEB RESOURCES

CDC-MMWR

Tularemia --- United States, 1990--2000

|

Erysipeloid- is an acute but very slowly evolving skin infection caused by

gram-positive bacillus (Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae).

©

Mount

Allison Science Image Collection

Erysipeloid- is an acute but very slowly evolving skin infection caused by

gram-positive bacillus (Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae).

©

Mount

Allison Science Image Collection |

ERYSIPELOID

This is an occupational disease of

butchers, meat processors, farmers, poultry workers, fish handlers: swine and

fish handlers are particularly at risk. The causative agent, Erysipelothrix

rhusiopathiae, is a Gram-positive anaerobic rod which infects through skin

abrasion while handling contaminated animal products or soil. Generally, the

organism produces an inflammatory skin lesion, on fingers or hand, which is

violaceus and has a raised edge. It spreads peripherally, as the discoloration

in the central area fades. The painful lesion is

pruritic and causes a burning

or throbbing sensation. It lacks suppuration and thus is distinguishable

from staphylococcal erysipelas. Diffuse cutaneous infection and septicemia are

rare. The organism can be cultured easily on most laboratory media. It is easily

treatable with penicillin.

|

|

|

Return to the Bacteriology Section

of Microbiology and Immunology On-line Return to the Bacteriology Section

of Microbiology and Immunology On-line

This page last changed on

Sunday, February 14, 2016

Page maintained by

Richard Hunt

|

Brucella abortus - Gram-negative, coccobacillus prokaryote; causes bovine spontaneous abortion due to its rapid growth in the presence of

erythritol (produced in the plancenta). SEM x 29,650

©

Dennis Kunkel Microscopy, Inc.

Used with permission

Brucella abortus - Gram-negative, coccobacillus prokaryote; causes bovine spontaneous abortion due to its rapid growth in the presence of

erythritol (produced in the plancenta). SEM x 29,650

©

Dennis Kunkel Microscopy, Inc.

Used with permission

Plague suits. The beak was filled with sweet smelling oils and vinegar

to counteract the smell of plague victims. Although physicians in the 1300's

did not know the cause of plague, the suits may have been effective to some

degree in that they kept fleas off and the shiny beak may have posed an

obstacle to the entry of fleas. Left From:

Bubonic Plague by Ely Janis Right:

©

Bristol Biomedical Image Archive, University of Bristol. Used with

permission

Plague suits. The beak was filled with sweet smelling oils and vinegar

to counteract the smell of plague victims. Although physicians in the 1300's

did not know the cause of plague, the suits may have been effective to some

degree in that they kept fleas off and the shiny beak may have posed an

obstacle to the entry of fleas. Left From:

Bubonic Plague by Ely Janis Right:

©

Bristol Biomedical Image Archive, University of Bristol. Used with

permission

Male Xenopsylla cheopsis (oriental rat flea) engorged with blood CDC

Male Xenopsylla cheopsis (oriental rat flea) engorged with blood CDC

Histopathology of spleen in fatal human plague - Necrosis and Yersinia

pestis. CDC/Dr. Marshall Fox

Histopathology of spleen in fatal human plague - Necrosis and Yersinia

pestis. CDC/Dr. Marshall Fox

Capillary fragility is one of the manifestations of a plague infection, evident here on the leg of an infected patient.

CDC

Capillary fragility is one of the manifestations of a plague infection, evident here on the leg of an infected patient.

CDC Plague patient displying a swollen axillary lymph node CDC

Plague patient displying a swollen axillary lymph node CDC Yersinia

pestis grows

well on most standard laboratory media, after 48-72 hours, grey-white to

slightly yellow opaque raised, irregular “fried egg” morphology;

alternatively colonies may have a “hammered copper” shiny

surface. CDC

Yersinia

pestis grows

well on most standard laboratory media, after 48-72 hours, grey-white to

slightly yellow opaque raised, irregular “fried egg” morphology;

alternatively colonies may have a “hammered copper” shiny

surface. CDC Anthrax skin lesion on face of man CDC

Anthrax skin lesion on face of man CDC

Mediastinal widening

and pleural effusion on chest X-ray in inhalational anthrax CDC

Mediastinal widening

and pleural effusion on chest X-ray in inhalational anthrax CDC

Infection of

macrophages or parenchymal cells by Listeria monocytogenes

Infection of

macrophages or parenchymal cells by Listeria monocytogenes

Thumb with skin ulcer of tularemia.

CDC/Emory U./Dr. Sellers

Thumb with skin ulcer of tularemia.

CDC/Emory U./Dr. Sellers

Erysipeloid- is an acute but very slowly evolving skin infection caused by

gram-positive bacillus (Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae).

©

Mount

Allison Science Image Collection

Erysipeloid- is an acute but very slowly evolving skin infection caused by

gram-positive bacillus (Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae).

©

Mount

Allison Science Image Collection