|

x |

x |

|

|

|

|

INFECTIOUS

DISEASE |

BACTERIOLOGY |

IMMUNOLOGY |

MYCOLOGY |

PARASITOLOGY |

VIROLOGY |

|

SPANISH |

BACTERIOLOGY - CHAPTER TWENTY

CHLAMYDIA AND

CHLAMYDOPHILA

Dr. Gene Mayer

Professor Emeritus

University of South Carolina School of Medicine

|

|

TURKISH |

|

SLOVAK |

|

ALBANIAN |

|

Let us know what you think

FEEDBACK |

|

SEARCH |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Logo image © Jeffrey

Nelson, Rush University, Chicago, Illinois and

The MicrobeLibrary |

|

TEACHING OBJECTIVES

To describe the developmental cycle of

chlamydia

To describe the pathogenesis, epidemiology and clinical

syndromes associated with chlamydia

KEY WORDS

Elementary bodies

Reticulate bodies

Inclusion

Biovar

Serovar

Trachoma

Inclusion

conjunctivitis

LGV

Reiter's syndrome

Psittacosis

Ornithosis

TWAR agent |

The family Chlamydiaceae consists of

two genera. One species

of Chlamydia

and two of Chlamydophila are important in causing disease in

humans.

-

Chlamydia trachomatis can

cause urogenital infections, trachoma, conjunctivitis, pneumonia and

lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV)

-

Chlamydophila pneumoniae can cause

bronchitis, sinusitis, pneumonia and possibly atherosclerosis

-

Chlamydophila psittaci can cause pneumonia (psittacosis).

Members of the Chlamydiaceae are small obligate

intracellular parasites and were formerly considered to be viruses. However, they

contain DNA, RNA and ribosomes and make their own proteins and nucleic acids and

are now considered to be true bacteria. They possess an inner and outer membrane

similar to gram-negative bacteria and a lipopolysaccharide but do not have a peptidoglycan layer.

Although they synthesize most of their metabolic intermediates, they are unable

to make their own ATP and thus are energy parasites.

Physiology and Structure

Elementary bodies (EB)

EBs are the small (0.3 - 0.4

μm) infectious form of the chlamydia. They possess a rigid outer

membrane that is extensively cross-linked by disulfide bonds. Because of

their rigid outer membrane the elementary bodies are resistant to harsh

environmental conditions encountered when the chlamydia are outside of their

eukaryotic host cells. The elementary bodies bind to receptors on host cells

and initiate infection. Most chlamydia infect columnar epithelial cells but

some can also infect macrophages.

Reticulate bodies (RB)

RBs are the non-infectious

intracellular from of the chlamydia. They are the metabolically active

replicating form of the chlamydia. They possess a fragile membrane lacking

the extensive disulfide bonds characteristic of the EB.

|

|

Figure 1 The developmental cycle of chlamydia

Figure 1 The developmental cycle of chlamydia

|

Developmental cycle (Figure 1) - The EBs bind to receptors on

susceptible cells and are internalized by endocytosis and/or by phagocytosis.

Within the host cell

endosome the EBs reorganize and become

RBs. The chlamydia

inhibit the fusion of the endosome with the lysosomes and thus resist

intracellular killing. The entire intracellular life cycle of the chlamydia

occurs within the endosome. RBs replicate by binary fission and reorganize

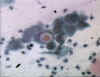

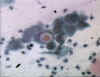

into EBs. The resulting inclusions may contain 100 - 500 progeny (Figure 2). Eventually,

the cells and inclusions lyse (C. psittaci) or the inclusion is

extruded by reverse endocytosis (C. trachomatis and C. pneumoniae)

(Figure 1).

|

|

Figure 2 Chlamydial inclusions © Bristol

Biomedical Archive. Used with permission

Figure 2 Chlamydial inclusions © Bristol

Biomedical Archive. Used with permission

Figure 3 Chlamydial inclusions in an endothelial

cell © Bristol Biomedical Archive. Used with permission

Figure 3 Chlamydial inclusions in an endothelial

cell © Bristol Biomedical Archive. Used with permission

Figure 4 Distribution of trachoma © World Health Organization

Figure 4 Distribution of trachoma © World Health Organization

|

Chlamydia trachomatis

C. trachomatis is

the causative agent of trachoma, urogenital disease, infant pneumonia

and

lymphogranuloma venereum.

Biovars

C. trachomatis has a limited host

range and only infects human epithelial cells (one strain can infect mice).

The species is divided into three

biovars (biological variants): trachoma,

lymphogranuloma venereum and mouse pneumonitis.

Serovars

The human biovars have been further

subdivided in to several serovars (serological variants; equivalent to

serotypes) that differ in

their major outer membrane proteins and which are associated with different

diseases (Table 1)

|

Table

1 |

|

Serovar

|

Disease

|

Distribution

|

|

A B Ba

C

|

Trachoma

|

Asia

and Africa

|

|

D - K

|

Disease

of eye and genitals:

Conjunctivitis

Urethritis

Cervicitis

Respiratory System:

Infant pneumonia

|

World

wide

|

|

LGV1

LGV2 LGV3

|

Lymphogranuloma

venerium

|

Worldwide

|

|

|

Figure 4A

Figure 4A

Chlamydia - Reported rates per 100,000 population by race/ethnicity: United States,1999

CDC

Figure 4B

Figure 4B

Chlamydia - Age-and gender-specific rates: United States,1999 CDC

Figure 5 Results of trachoma-specific

interventions in three countries in the last 30 years

Figure 5 Results of trachoma-specific

interventions in three countries in the last 30 years

© World Health Organization |

Pathogenesis and Immunity

C. trachomatis

infects non-ciliated columnar epithelial cells. The organisms stimulate the

infiltration of polymorphonuclear cells and lymphocytes which leads to

lymphoid follicle formation and fibrotic changes. The clinical

manifestations result from destruction of the cells and the host

inflammatory response. Infection does not stimulate long lasting immunity

and reinfection results in a inflammatory response and subsequent tissue

damage.

Epidemiology

a. C. trachomatis (biovar: trachoma) is found

worldwide primarily in areas of poverty and overcrowding (Figure 4). It is

estimated that 500 million people are infected worldwide and 7 - 9

million people are blind as a consequence. C. trachomatis biovar:

trachoma is endemic in Africa, the Middle East, India and Southeast

Asia. In the United States, Native Americans are most commonly

infected.

Infections occur most commonly in children. The organism can be

transmitted by droplets, hands, contaminated clothing, flies, and by

passage through an infected birth canal.

a. C. trachomatis (biovar: trachoma) is the

most common sexually transmitted bacterial disease in the United States

(4 million new cases each year) and 50 million new cases occur yearly

worldwide. In the United States, the highest infection rates occur in

Native and African Americans (Figure 4A) with a peak incidence in the

late teens/early twenties (Figure 4B).

b. C. trachomatis (biovar: LGV) is a sexually

transmitted disease that occurs sporadically in the United States but is

more prevalent in Africa, Asia and South America. Humans are the only

natural host. Incidence is 300 - 500 cases per year in the United States

with male homosexuals being the major reservoir of the disease.

|

|

|

|

Figure 7 Chlamydial kerato-conjunctivitis © Bristol

Biomedical Archive. Used with permission

Figure 7 Chlamydial kerato-conjunctivitis © Bristol

Biomedical Archive. Used with permission

Figure 8

Figure 8

Tracomatous SCARRING :

the presence of scarring in the tarsal conjunctiva. Scars are easily visible as white lines, bands, or sheets in the tarsal conjunctiva. They are glistening and fibrous in appearance. Scarring, especially diffuse

fibrosis, may obscure the tarsal blood vessels.

©

World Health Organization

Tracomatous TRICHIASIS : at least one eyelash rubs on the

eyeball © World Health

Organization

Tracomatous TRICHIASIS : at least one eyelash rubs on the

eyeball © World Health

Organization

CORNEAL OPACITY : easily visible corneal opacity over the

pupil. The pupil margin is blurred viewed through the opacity. Such corneal opacities cause significant visual impairment (less tah 6/18 or 0.3

vision) © World Health

Organization

CORNEAL OPACITY : easily visible corneal opacity over the

pupil. The pupil margin is blurred viewed through the opacity. Such corneal opacities cause significant visual impairment (less tah 6/18 or 0.3

vision) © World Health

Organization |

Clinical Syndromes

Chronic infection or repeated reinfection

with C. trachomatis (biovar: trachoma) results in inflammation and

follicle formation involving the entire conjunctiva (Figure 7 and 8). Scarring of the

conjunctiva causes turning in of the eyelids and eventual scarring,

ulceration and blood vessel formation in the cornea, resulting in

blindness. The name trachoma comes from 'trakhus' meaning rough

which characterizes the appearance of the conjunctiva. Inflammation in the

tissue also interferes with the flow of tears which is an important

antibacterial defense mechanisms. Thus, secondary bacterial infections

occur.

Inclusion conjunctivitis

is caused by C. trachomatis (biovar: trachoma) associated with

genital infections (serovars D - K). The infection is characterized by a

mucopurulent

discharge, corneal infiltrates and occasional corneal

vascularization. In chronic cases corneal scarring may occur. In neonates

infection results from passage through an infected birth canal and becomes

apparent after 5 - 12 days. Ear infection and rhinitis can accompany the

ocular disease.

Infants infected with C.

trachomatis (biovar: trachoma; serovars: D - K) at birth can develop

pneumonia. The children develop symptoms of wheezing and cough but not

fever. The disease is often preceded by neonatal conjunctivitis.

Infection with the LGV serovars of

C. trachomatis (biovar: LGV) can lead to

oculoglandular conjunctivitis. In addition to the conjunctivitis, patients

also have an associated lymphadenopathy.

In females, the infection is

usually (80%) asymptomatic but symptoms can include cervicitis, urethritis,

and salpingitis. Postpartum fever in infected mothers is common. Premature

delivery and an increased rate of ectopic pregnancy due to

salpingitis can

occur. In the United States, tubal pregnancy is the leading cause of first-trimester, pregnancy-related deaths.

In males, the infection is usually (75%) symptomatic

After a 3 week incubation period patients may develop urethral discharge,

dysuria and

pyuria.

Approximately 35 - 50% of non-gonococcal urethritis is due to C.

trachomatis (biovar: trachoma). Post-gonococcal urethritis also occurs

in men infected with both Neisseria gonorrhoeae and C.

trachomatis. The symptoms of chlamydial infection occur after

treatment for gonorrhea because the incubation time is longer.

Up to 40% of women with untreated (undiagnosed) chlamydia will develop

pelvic inflammatory diseases and about 20% of these women will become

infertile. Many untreated cases (18%) result in chronic pelvic pain.

Women infected with chlamydia have a 3 - 5 fold increased risk of acquiring HIV.

|

|

Figure 9 Chlamydial urogenital infection in men. After an incubation of

3 weeks, up to 75% of patients show symptoms such as urethral discharge, dysuria and

pyuria

Figure 9 Chlamydial urogenital infection in men. After an incubation of

3 weeks, up to 75% of patients show symptoms such as urethral discharge, dysuria and

pyuria

|

Reiter's syndrome is a triad of

symptoms that include conjunctivitis,

polyarthritis and genital

inflammation. The disease is associated with HLA-B27. Approximately 50 -

65% of patients have an acute C. trachomatis infection at the onset

of arthritis and greater than 80% have serological evidence for C.

trachomatis infection. Other infections (shigellosis or Yersinia

enterocolitica) have also been associated with Reiter's syndrome.

The primary lesion of LGV is a small painless and

inconspicuous vesicular lesion that appears at the site of infection,

often the penis or vagina. The

patient may also experience fever, headache and myalgia. The second stage

of the disease presents as a marked inflammation of the draining lymph

nodes. The enlarged nodes become painful 'buboes' that can eventually

rupture and drain. Fever, headache and myalgia can

accompany the inflammation of the lymph nodes. Proctitis is common in

females; lymphatic drainage from the vagina is perianal. Proctitis in

males results from anal intercourse or from lymphatic spread from the

urethra. The course of the disease is variable but it can lead to genital

ulcers or elephantiasis due to obstruction of the lymphatics.

|

|

|

Laboratory diagnosis

There are several laboratory

tests for diagnosis of C. trachomatis but the sensitivity of the

tests will depend on the nature of the disease, the site of specimen

collection and the quality of the specimen. Since chlamydia are

intracellular parasites, swabs of the involved sites rather than exudate

must be submitted for analysis. It is estimated that as many as 30% of the

specimens submitted for analysis are inappropriate.

Examination of stained cell scrapings for

the presence of inclusion bodies (Figures 2 and 3) has been used for diagnosis but this

method is not as sensitive as other methods.

Culture is the most specific method for

diagnosis of C. trachomatis infections. Specimens are added to

cultures of susceptible cells and the infected cells are examined for the

presence of iodine-staining inclusion bodies.

Iodine stains glycogen in the inclusion bodies. The presence of

iodine-staining inclusion bodies is specific for C. trachomatis

since the inclusion bodies of the other species of chlamydia do not

contain glycogen and stain with iodine.

Direct immunofluorescence and

ELISA kits that detect the group specific LPS or strain-specific outer

membrane proteins are available for diagnosis. Neither is as good as

culture, particularly with samples containing few organisms (e.g.

asymptomatic patients).

Serological tests for diagnosis

are of

limited value in adults, since the tests do not distinguish between

current and past infections. Detection of high titer IgM antibodies is

indicative of a recent infection. Detection of IgM antibodies in neonatal

infection is useful.

Three tests based on

nucleic acid probes are available. These tests are sensitive and specific

and may replace culture as the method of choice.

Treatment and prevention

Tetracyclines, erythromycin

and sulfonamides are used for treatment but they are of limited value in

endemic areas where reinfection is common. Vaccines are of little value and

are not used. Treatment coupled with improved sanitation to prevent

reinfection is the best way to control infection. Safe sexual practices and

prompt treatment of symptomatic patients and their sexual partners can

prevent genital infections.

|

|

|

Chlamydophila psittaci

C. psittaci is the

causative agent of psittacosis (parrot fever). Although the disease was

first transmitted by parrots, the natural reservoir for C. psittaci can be any species of bird. Thus, the disease has also been called ornithosis

from the Greek word for 'bird'.

Pathogenesis

The respiratory tract is the main

portal of entry. Infection is by inhalation of organisms from infected birds

or their droppings. Person-to-person transmission is rare. From the lungs

the organisms enter the blood stream and are transported to the liver and

spleen. The bacteria replicate at these sties where they produce focal areas

of necrosis. Hematogenous seeding of the lungs and other organs then occurs.

A lymphocytic inflammatory response in the alveoli and interstitial spaces

leads to edema, infiltration of macrophages, necrosis and sometimes

hemorrhage. Mucus plugs may develop in the alveoli causing cyanosis and

anoxia.

Epidemiology

Approximately 50 - 100 cases of

psittacosis occur annually in the United States with most infections

occurring in adults. The organism is present in tissues, feces and feathers

of infected birds that are symptomatic or asymptomatic. There may also be

reservoirs in other animals such as cats and cattle. Veterinarians, zoo

keepers, pet shop workers and poultry processing workers are at increased

risk for developing the disease.

|

|

|

|

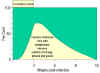

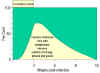

Figure 10 Course of psittacosis. In severe disease there is a 5%

mortality rate

Figure 10 Course of psittacosis. In severe disease there is a 5%

mortality rate |

Clinical Syndromes

The illness develops after an

incubation time of 7 - 15 days. Symptoms include fever, chills, headache, a

non-productive cough and a mild

pneumonitis. In uncomplicated cases the

disease subsides by 5-6 weeks after infection. Asymptomatic infections are

common. In complicated cases convulsions, coma and death (5% mortality rate)

can occur. Other complications include carditis, hepatomegaly and

splenomegaly (Figure 10).

Laboratory diagnosis

Laboratory diagnosis is based

on a serological tests. A four-fold rise in titer in paired samples in a

complement fixation test is indicative of infection.

Treatment and prevention

Tetracycline or

erythromycin are the antibiotics of choice. Control of infection in birds by

feeding of antibiotic supplemented food is employed. No vaccine is

available.

|

|

|

Chlamydophila pneumoniae

Chlamydophila pneumoniae is the causative agent of

an atypical pneumonia (walking pneumonia) similar to those caused by Mycoplamsma

pneumoniae and Legionella pneumoniae. In addition it can cause a

pharyngitis, bronchitis, sinusitis and possibly atherosclerosis. The organism

was originally called the TWAR strain from the names of the two original

isolates - Taiwan (TW-183) and an acute respiratory isolate designated AR-39.

It is now considered a separate species of chlamydia.

Pathogenesis

The organism is transmitted person-

to-person by respiratory droplets and causes bronchitis, sinusitis and

pneumonia.

Epidemiology

The infection is common with 200,000 -

300,000 new cases reported annually, mostly in young adults. Although 50% of

people have serological evidence of infection most infections are

asymptomatic or mild. The disease is most common in military bases and

college campuses (crowding). No animal reservoir has been identified.

Potential link to

atherosclerosis: A report

in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology

documented a high incidence of C. pneumoniae in the arteries of

patients with atherosclerosis (79% compared with 4% in the control group).

It is still unproven that the link is causal. However, previous reports

show a high association between presence of antibodies to C. pneumoniae

in serum of patients with atherosclerosis as well as the presence of the

organisms in the coronary and carotid arteries.

Clinical Syndrome

Symptoms include a pharyngitis,

bronchitis, a persistent cough and malaise. More severe infections can

result in pneumonia, usually of a single lobe.

Laboratory diagnosis

Culture is difficult so

serological test are most common. A four-fold rise in titer in paired

samples is diagnostic.

Treatment and prevention

Tetracycline and

erythromycin are the antibiotics of choice. No vaccine is available.

|

|

|

Return to the Bacteriology Section

of Microbiology and Immunology On-line Return to the Bacteriology Section

of Microbiology and Immunology On-line

This page last changed on

Sunday, March 06, 2016

Page maintained by

Richard Hunt

|