| x | x | |||||

|

||||||

| BACTERIOLOGY | IMMUNOLOGY | MYCOLOGY | PARASITOLOGY | VIROLOGY | ||

|

||||||

|

Let us know what you think FEEDBACK |

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Necrotizing Infections of Skin, Fascia, and Muscle Necrotizing infections of skin, fascia, and muscle form a diverse group of syndromes that have in common the urgent need to begin antibiotic therapy and to seek surgical consultation. These syndromes should be considered whenever tissue injury to the skin or subcutaneous tissue is accompanied by any combination of blebs, bullae, crepitance, dusky coloration, marked swelling, disproportionate pain, or systemic toxicity. Necrotizing fasciitis caused by group A streptococci has received the most attention in recent years as “the flesh-eating bacteria syndrome,” but many processes fit into this broad category. Diverse etiology and confusing nomenclature characterize this group of infections. These infections are often but not always preceded by some form of trauma or surgery. With respect to the causative bacteria, three are three broad categories: Mixed aerobic and anaerobic, group A streptococcal, and clostridial. Mixed aerobic and anaerobic infection accounts for up to 47% of cases. The syndromes include non-clostridial anaerobic cellulitis, synergistic necrotizing cellulitis, cervical necrotizing fasciitis, and type I necrotizing fasciitis. All of these syndromes―and also Fournier’s gangrene which can be viewed as a subset of type I necrotizing fasciitis that involves the perineum, lower abdominal wall, gluteal area, and (in males) the scrotum and penis―are more common in patients with diabetes mellitus. Group A streptococci (S. pyogenes) cause type II necrotizing fasciitis, previously known as “streptococcal gangrene.” This form of necrotizing fasciitis has become much more common in recent years, probably because of an increased frequency of streptococcal strains (notably, M types 1 and 3) that produce pyrogenic exotoxins. Many of these cases occur in young, previously-healthy persons. There is often a history of blunt or penetrating trauma, childbirth, varicella (chickenpox), or injecting drug use. It has been suggested but not proven that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) predispose to this infection and also mask its severity. Clostridial infections of skin and soft tissues is responsible for two clinical syndromes: clostridial cellulitis (anaerobic cellulitis) and clostridial myonecrosis (true gas gangrene). The presence of clostridial species in wounds often represents simple contamination and is of no clinical consequence. Clostridia multiply and cause disease in tissue environments made anaerobic by ischemia, necrosis, or foreign bodies. Clostridium perfringens, which produces at least 12 identified toxins, is the most common cause of necrotizing infection, but other species (such as C. novyi, C. histolyticum, and C. septicum) are also important. The above categories are by no means exhaustive. Vibrio vulnificus can cause necrotizing soft tissue infection in wounds exposed to salt water, and Aeromonas hydrophila can do the same in wounds exposed to fresh water. Meleney’s synergistic gangrene, for example, is a rare but distinctive infection in which S. aureus and microaerophilic streptococci combine to cause a relentlessly progressive wound infection. In some studies, Pseudomonas aeruginosa has been found to play an important role in Fournier’s gangrene, a necrotizing infection of the perineum and, in men, of the external genitalia. |

|||||

|

||||||

|

Sphenoid Sinusitis Acute sphenoid sinusitis is a life-threatening cause of “the worst headache ever.” Diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion and CT scan of the paranasal sinuses. The sphenoid sinuses and their venous drainage are intimately related to the same structures that surround the cavernous sinus (see chapter on Central Nervous System Infections): namely, the brain, pituitary, carotid artery, and several cranial nerves. Infection of the sphenoid sinuses can occur in the setting of chronic sinusitis or acute pansinusitis or can be an isolated event with no apparent cause. Cocaine snorting may be a risk factor. Although the classic headache of sphenoid sinusitis localizes to the vertex of the skull, other pain patterns are more common. Unilateral facial pain is sometimes caused by irritation of one or more branches of the Vth cranial nerve. The pain can also radiate to the temporal or occipital areas or can be a severe, generalized, “pan-cephalic” headache. Other clinical signs of sinusitis such as nasal drainage or postnasal drip are variably present. Diagnosis of sphenoid sinusitis is made by imaging studies. The sphenoid sinuses can be seen on lateral x-rays of the skull, but are better visualized by CT scan. |

||||||

|

Pericarditis and Myocarditis Both pericarditis and myocarditis have been associated with a large number of viruses and bacteria, as well as with fungi and parasites. In the United States, most cases are eventually called “idiopathic” and presumed due to viruses. Enteroviruses, especially the coxsackieviruses, are frequently associated with both diseases. Other viruses reported to cause both pericarditis and myocarditis include influenza viruses, echoviruses, adenoviruses, mumps, Epstein-Barr virus, varicella-zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, and hepatitis B. Similarly systemic bacterial infections - for example, meningococcemia, staphylococcal or streptococcal bacteremia, or Legionella pneumophila infection - can similarly involve the myocardium, pericardium, or both. Myocarditis occurs in about 30% of persons infected with Trypanosoma cruzi (the cause of Chagas disease), which is endemic in parts of Latin America. Mycobacterium tuberculosis is an extremely important cause of pericarditis, which can also be caused by the agents of “regional mycosis” encountered in the United States (that is, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, and coccidioidomycosis). |

||||||

|

Aortitis and Mycotic Aneurysm Mycotic aneurysm of the aorta is most commonly due to non-typhoidal Salmonella species. Mortality is high if the disease is unrecognized. Gastroenteritis resulting from ingestion of Salmonella probably causes a transient bacteremia in many patients that usually resolves without treatment. However, these organisms have an affinity for atherosclerotic plaques. Multiplication in atherosclerotic plaques leads to weakening of the aortic wall and formation of an aneurysm. The usual patient is an older adult, most commonly a man, with risk factors for significant atherosclerosis such as diabetes mellitus or hypertension. Some affected patients have underlying peptic ulcer disease, treatment of which usually raises the gastric pH thereby lowering the patient's resistance to ingested Salmonella organisms. Others have a condition that impairs the ability of macrophages to clear the bloodstream of Salmonella, such as cirrhosis or a condition requiring immunosuppressive drugs. Onset of symptoms is commonly insidious. In a recent study, the average duration of symptoms was about one month (range of 1 day to 6 months). Nearly all patients present with fever and pain in the abdomen, back, or both. Results from three clinical series suggest that about 10% of persons > 50 years with non-typhi Salmonella bacteremia develop mycotic aneurysm. The diagnosis of aortitis with or without mycotic aneurysm is made most easily by CT scan with contrast enhancement. The diagnosis can also be made by arteriography. Most aneurysms are found in the abdominal aorta, typically below the renal arteries. The thoracic aorta is involved in about 17% of patients. Blood cultures are usually positive (85% of patients) and stool cultures are frequently positive (64% of patients). Definitive diagnosis is made at surgery. Aortitis with aortic aneurysm is probably uniformly fatal without treatment, rupture of the aneurysm being the usual cause of death.

|

||||||

|

Acute Epiglottitis (Supraglottitis) Acute epiglottitis (or supraglottitis) is a life-threatening cellulitis of the epiglottis and adjacent structures occurring mainly in children, usually due to Haemophilus influenzae, and with the potential for sudden, complete obstruction of the airway. It is a medical emergency, and must be distinguished from croup. H. influenzae type B is the usual pathogen in both children and adults, but occasional cases result from S. pneumoniae, S. aureus (including methicillin-resistant strains), streptococci, Haemophilus paraphrophilus, and numerous bacterial species and viruses. The incidence of the disease in children has decreased markedly since the introduction of the H. influenzae type b conjugated vaccine. Epiglottitis can also be a noninfectious illness caused by allergic reactions, physical agents, smoking recreational drugs, or as a complication of tonsillectomy. The process consists of a diffuse cellulitis of the supraglottic tissues (hence “supraglottitis” may be the more accurate term). The onset in children is usually sudden with fever, dysphonia, dysphagia, and difficulty breathing. The child characteristically leans forward and drools, with tentative respirations. Adults are more likely to present with a severe sore throat, odynophagia, and a sensation of airway obstruction. The major differential diagnosis in children is croup. Croup usually has a more gradual onset, often preceded by an upper respiratory infection. Also, children with croup prefer to lie supine and typically do not have drooling or dysphagia. Likewise, patients with epiglottitis (unlike those with croup) seldom have a barking cough or aphonia. The diagnosis can be made by observing a “thumb sign” (i.e., swelling causes it to resemble a thumb, whereas the normal epiglottis resembles a finger). In children, however, there is concern that (1) vigorous attempt to visualize the epiglottis can precipitate airway obstruction or vagally-mediated cardiopulmonary arrest, and (2) sending the patient for an x-ray can be a fatal error since complete airway obstruction can develop within minutes. In children, the mortality from acute epiglottitis with airway obstruction is 80%. Mortality is much lower in adults (<5 % in some series), but fatalities occur. |

||||||

Figure

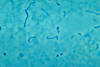

Figure phase-contrast photomicrographic image of Fusobacterium necrophorum.

|

Soft-Tissue Infections of the Head and Neck Several distinctive syndromes of life-threatening deep cervical infection are best understood in terms of the complex anatomy of the fascial layers, spaces, and potential spaces of that region. Deep infections of the head and neck usually begin when bacteria indigenous to the mouth or oropharynx gain access to deeper tissues and fascial planes by way of dental infection, severe tonsillitis or pharyngitis, or perforation caused by foreign bodies such as fish bones or chicken bones. Ludwig’s angina, which arises from the floor of the mouth often as a result of infection involving the second or third mandibular molars, presents with fever, difficulty eating and swallowing, and a brawny or “woody” swelling in the sub-mandibular space. Patients complain of difficulty eating and swallowing. The mouth is often held open and the tongue pushed upward to the palate. The basic problem is a rapidly spreading cellulitis that can progress to airway obstruction and asphyxia. Lateral pharyngeal space infection arises from dental infection, otitis media, mastoiditis, parotitis, tonsillitis, or pharyngitis. Patients with involvement of the anterior compartment present with fever, chills, and dysphagia accompanied by severe pain, trismus, and swelling with tenderness just below the angle of the mandible. Patients with involvement of the posterior compartment present with sepsis. Involvement of the posterior compartment causes less pain but is more treacherous; extension to the larynx can cause respiratory obstruction and extension into the carotid sheath can cause erosion of the internal carotid artery and thrombosis of the internal jugular vein. Retropharyngeal space infection arises as an extension from infection in the lateral pharyngeal space, from infection involving the retropharyngeal lymph nodes, or from perforation of the pharynx by a foreign body. Fever, chills, dysphagia, dyspnea, and neck pain are common presenting complaints. Examination may reveal bulging of the posterior pharyngeal wall, and spread to the lateral pharyngeal space causes swelling usually localized to one side of the neck. Again, there is the potential for extension into the carotid sheath. Cervical prevertebral space infection, which is less common, usually occurs as a complication of osteomyelitis involving the cervical spine. The associated prevertebral abscess is usually contained by the prevertebral fascia, and therefore the external neck swelling characteristic of lateral pharyngeal and retropharyngeal space infections does not occur. Septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, known as the Lemierre syndrome, arises by extension of any oropharyngeal or odontogenic infection into the carotid sheath. Patients present with fever, chills, prostration, and tenderness along the sternocleidomastoid muscle. This syndrome is most commonly due to Fusobacterium necrophorum, an anaerobic gram-negative rod capable of causing severe sepsis. The full syndrome is characterized by septic pulmonary emboli and sometimes by metastatic infection in distant organs. These and other soft-tissue infections of the head and neck are usually suggested by the history and by localized swelling on physical examination, but at times the presentation can be subtle. Easily-overlooked physical findings include localized tenderness over the cervical spine (prevertebral space infection due to osteomyelitis) and tenderness along the sternocleidomastoid (Lemierre syndrome). Lateral x-ray of the cervical spine shows widening of the retropharyngeal space in patients with retropharyngeal and prevertebral space infections (the two spaces cannot be distinguished on plain x-ray). Newer imaging procedures (CT and MRI) greatly facilitate precise anatomic diagnosis. Blood cultures should be obtained and are usually positive in the Lemierre syndrome. Complications of these syndromes include respiratory obstruction and asphyxiation (especially with Ludwig’s angina and infection of the lateral pharyngeal or retropharyngeal spaces), thrombosis of the internal vein, erosion of the internal carotid artery, extension into the mediastinum, and severe sepsis. Untreated, all of these syndromes carry high mortality rates. |

|||||

This baby has neonatal tetanus. It is

completely rigid.

Tetanus kills most of the babies who get it.

Infection usually happens when newly cut umbilical cord

is exposed to dirt CDC

This baby has neonatal tetanus. It is

completely rigid.

Tetanus kills most of the babies who get it.

Infection usually happens when newly cut umbilical cord

is exposed to dirt CDC This baby has tetanus. He cannot breast feed or open his mouth

because the muscles in his face have become so tight

WHO

This baby has tetanus. He cannot breast feed or open his mouth

because the muscles in his face have become so tight

WHO Severe case of adult tetanus. The muscles in the back and legs are very tight.

Muscle spasms can break bones

CDC

Severe case of adult tetanus. The muscles in the back and legs are very tight.

Muscle spasms can break bones

CDC

|

Tetanus Tetanus affects more than 100 persons in the United States and is a significant problem in developing nations. There are four forms of the disease, as follows: generalized tetanus presenting with trismus or “lockjaw,” localized tetanus presenting as rigidity of muscles at or near the site of the causative organism (Clostridium tetani), cephalic tetanus affecting the muscles innervated by the cranial nerves, and neonatal tetanus originating in the umbilical stump of infants whose mothers are inadequately immunized. Most cases in the United States now occur in older persons, especially women. All of the manifestations of tetanus are attributed to a toxin, tetanospasmin, produced by C. tetani after its introduction into a wound. C. tetani is a gram-positive, “tennis racket”-shaped anaerobic bacillus capable of surviving indefinitely in the environment in its spore form. Injuries leading to tetanus are often trivial and indeed are inapparent or not remembered by the patient in about one-quarter of cases. The precise mechanism by which tetanospasmin disrupts the nervous system remains unknown, but it is clear it blocks neurotransmitter release mainly from inhibitory neurons. Removal of the inhibitory influence on excitatory neurons causes the rigidity and spasms that define the disease. Tetanospasmin also has a major effect on the autonomic nervous system, causing a hypersympathetic state explained in part by loss of the normal inhibition to catecholamine release by the adrenal glands. Generalized tetanus most often begins with rigidity of the masseter muscles causing “lockjaw” with trismus and risus sardonicus (that is, a sinister-looking, unintentional smile). This is followed by generalized spasms with opisthotonous (arching of the back, flexing of arms, and extension of the legs). Spasms can cause death by airway obstruction or spasm of the diaphragm. Localized tetanus affecting muscles other than those supplied by the cranial nerves (cephalic tetanus) is usually a milder form of the disease but can progress to generalized tetanus. Neonatal tetanus usually begins with weakness and failure to thrive followed alter by rigidity and spasms. Tetanus is a clinical diagnosis. Most but not all patients lack protective titers of anti-tetanus antibodies, but laboratory tests neither confirm nor exclude the diagnosis of tetanus. The most frequent diagnosis to exclude is dystonic reaction to neuroleptic drugs (such as phenothiazines) or other central dopamine antagonists. Facial spasms and expressions in patients with dystonic reactions often resemble tetanus. Patients with dystonic reactions tend to turn their heads laterally during spasms (which is rare in patients with tetanus) and often respond rapidly to therapy with diphenhydramine (Benadryl®) or benztropine. Strychnine poisoning can be confused with tetanus and therefore blood and urine samples should be obtained for assays for strychnine. Dental infections can cause trismus but not the other manifestations of tetanus. The mortality from tetanus currently ranges from 6% in cases of mild tetanus to greater than 90% in neonatal tetanus. In severe generalized tetanus, mortality remains about 30% to 60% even with specialized care. |

|||||

Figure

FigureWound botulism involvement of compound fracture of right arm. 14-year-old boy fractured his right ulna and radius and subsequently developed wound botulism. CDC

|

Botulism Botulism, caused by an extremely potent neurotoxin produced by Clostridium botulinum, affects about 110 persons in the United States each year. Four forms of the disease are currently recognized: infant botulism, which accounts for about 72% of recent cases; food-borne botulism (25% of cases); wound botulism (3% of cases); and adult infectious botulism (rare). The hallmark of botulism consists of cranial nerve palsies and symmetric descending weakness. Early suspicion of the disease is mandatory in order to prevent death due to respiratory paralysis. C. botulinum, widely distributed in nature, is a gram-positive, spore-forming, strictly-anaerobic bacillus. The spores, although heat-resistant, are destroyed by a temperature of 120 degrees C sustained for five minutes. The organism is capable of causing localized infections including abscesses, but disease manifestations are nearly always caused by its neurotoxin. Eight types of botulinum toxin based on antigenic differences are currently recognized. Types A and B commonly cause food-borne botulism and wound botulism, types A, B, and F commonly cause infant botulism, and type E is often associated with botulism attributed to fish products. Once in the body, botulinum toxin spreads from the bloodstream to presynaptic nerve terminals, where it irreversibly blocks the release of acetylcholine. All forms of botulism feature bilateral cranial nerve palsies and descending paralysis, but the clinical features vary according to the mode of acquisition (that is, the form of botulism) and to a lesser extent according to the type of toxin. Infant botulism, caused by multiplication of C. botulinum in the neonatal gastrointestinal tract, often begins with failure to thrive, irritability, weak cry, drooling, and hypotonia. Dry mucous membranes, fecal and urinary retention, and a labile blood pressure are often present early in the course of the disease and reflect involvement of the autonomic nervous system. Foodborne botulism, caused by ingestion of pre-formed toxin, similarly begins with nonspecific symptoms such as dry mouth, sore throat, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain typically develop 12 to 36 hours (range several hours to one week) after ingestion of inadequately cooked food. Wound botulism, caused by wound contamination with C. botulinum, usually lacks prodromal symptoms. Adult infectious botulism is similar to infant botulism in its cause and presentation but is rare, since the normal flora of the adult gastrointestinal tract resists colonization by C. botulinum. Botulism should be suspected in any patient with symmetric peripheral nerve palsies and descending paralysis. Suggestive exposure histories include the ingestion of raw honey (in cases of infant botulism), home-canned vegetables, and injecting drug use especially with “black tar” heroin (wound botulism). Clinical features that are variably present and support the diagnosis include blurred vision, diplopia, dilated pupils, dry mouth with furrowed tongue, dysphagia, and weakness of the upper and lower extremities. Although the toxin enters the central nervous system, most patients are mentally alert and responsive at least when first seen. Fever is a feature of the disease only in wound botulism. In contrast to tetanus, sympathetic hyperreactivity does not occur and therefore the heart rate is normal or even slow and the blood pressure remains normal. The differential diagnosis of botulism includes tick paralysis (see above), myasthenia gravis and the Lambert-Eaton syndrome (both of which usually evolve more slowly and which lack autonomic symptoms and signs), the Miller Fisher variant of acute inflammatory polyneuropathy (which, unlike classic Guillain-Barré syndrome, often begins with cranial nerve palsies; however, there is prominent ataxia which does not occur in botulism); magnesium intoxication, organophosphate poisoning, brain stem infarction, and diphtheria. Sepsis, meningitis, and encephalitis need to be considered especially in infant botulism. When botulism is suspected, the patient should be admitted to the hospital and health authorities should be contacted. Serum should be obtained for assays for botulinum toxin. Stool samples and any implicated food should be obtained for toxin assays and anaerobic culture.

|

|||||

|

Capillary fragility is one of the manifestations of a plague infection, evident here on the leg of an infected patient.

CDC

Capillary fragility is one of the manifestations of a plague infection, evident here on the leg of an infected patient.

CDC

|

Plague Plague remains endemic in certain areas of the American Southwest as well as in other countries. It should be suspected whenever a patient with unexplained fever and toxicity gives a history of outdoors activities in any of the Four Corners states (Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah) or southern California. Prompt initiation of antibiotic therapy dramatically lowers the mortality. Yersinia pestis, the causative bacillus, resides among rodents and is transmitted from rodent to rodent or from rodent to a human by various fleas. Although rats continue to be the most important reservoirs in most countries where plague remains endemic, the major reservoirs in the United States are ground squirrels, rock squirrels, and prairie dogs. Humans usually acquire the disease when bitten by fleas that have previously fed on infected rodents. The disease can also be acquired by exposure (direct contact or inhalation) to infected animal tissues or fluids or by contact with a person with the pneumonic form of the disease. In addition, cases in the United States have now been traced to exposure to domestic cats with pneumonia or submandibular abscesses. In the United States, a majority of cases (about 60%) occur in persons under 20 years of age. Bubonic plague, the most common form of the disease, usually begins with sudden onset of fever, chills, and headache followed within 24 hours by intense localized pain that corresponds to an infected lymph node (bubo). The femoral and inguinal nodes are most often affected, but involvement of the axillary and cervical nodes is also common. Symptoms rapidly progress toward prostration, seizures, hypotension, and shock. High-grade bacteremia (that is, large numbers of bacilli in the blood) is present in advanced cases, but the term “septicemic plague” is usually reserved for cases of plague without an obvious bubo. Pneumonic plague is usually caused by hematogenous seeding of the lungs from a bubo, but occasionally occurs as a result of inhalation. Symptoms include cough, chest pain, and hemoptysis; the radiographic pattern varies from patchy bronchopneumonia to dense consolidation. Plague can also present as meningitis, pharyngitis, and gastroenteritis. Accurate diagnosis is made by obtaining a smear and culture from an aspirate of a bubo. The technique for aspiration involves injecting a small amount (about 1 cc) of sterile saline without preservative into the involved node using a 10-mL syringe and a 19- or 20- gauge needle and then aspirating back until the saline in the syringe becomes blood-tinged. Y. pestis can be isolated from blood cultures in many cases of bubonic plague and in virtually all cases of septicemic plague, and can be isolated from sputum in cases of pneumonic plague. A retrospective diagnosis of plague can be made serologically using paired serum samples obtained during the acute and convalescent phases. The mortality for plague without treatment is estimated to be greater than 50 percent.

|

|||||

Transmission electron micrograph of a virus that causes Hantavirus pulmonary

syndrome (Sin Nombre virus). CDC/Cynthia Goldsmith

Transmission electron micrograph of a virus that causes Hantavirus pulmonary

syndrome (Sin Nombre virus). CDC/Cynthia Goldsmith

Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome Clinical Progression

CDC

Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome Clinical Progression

CDC

Histopathology of hanatvirus pulmonary syndrome Other Organs

CDC

Histopathology of hanatvirus pulmonary syndrome Other Organs

CDC |

Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome First described in 1993 as a cluster of cases of severe pneumonia acquired in the Four Corners region of the southwestern United States, disease caused by Hantaviruses has now been described in many other parts of the U.S. This illness carries a 50% case-fatality rate. The major cause of the Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome in the United States is a recently-described Hantavirus called the Sin Nombre virus. Related Hantaviruses include the Bayou virus in Texas and Louisiana, the New York Virus in New York and Rhode Island, and the Black Creek Canal virus in Florida. and. Other Hantaviruses cause disease in South America. Transmission of the disease to humans seems to occur mainly by inhaling aerosolized excreta of rodents, who provide the key reservoir for Hantaviruses. Rodents implicated to date include the deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus) in the southwestern United States, the white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus) in the northeastern United States, the rice rat (Oryzomys palustrus) in Louisiana, and the cotton rat (Sigmodon hispidus) in Florida. Person-to-person transmission has not been observed in the United States but has not been entirely excluded, since such transmission was strongly suspected in several instances of Hantavirus disease in Argentina. The disease has an incubation period of about three weeks. The virus appears to attack endothelial cells and platelets in such a way as to cause widespread capillary leak. The first symptoms are usually fever malaise, and myalgia, sometimes accompanied by headaches and gastrointestinal symptoms. This prodrome resembles numerous viral syndromes. Cough is not necessarily present. About three to six days after the onset of prodromal symptoms, patients develop the rapid onset of hypotension with pulmonary edema. Within 48 hours nearly all patients have evidence of pulmonary edema on chest x-ray, with progresses rapidly and includes significant pleural effusions. Laboratory studies show marked leukocytosis with a left shift and hemoconcentration. Thrombocytopenia may be present and the partial thromboplastin time. The key to diagnosis is a high index of suspicion in an illness characterized by hypotension and pulmonary edema in a patient who has had out-of-doors exposure. Vector histories might include exploring poorly-ventilated spaces such as caves or seldom-used buildings. Confirmation is usually made by demonstrating Hantavirus-specific IgM antibodies; this test is considered to be diagnostic. Acute and convalescent serologies show a fourfold rise in IgG titers to Hantaviruses. The case-fatality rate is about 50%.

|

|||||

|

Infant with smallpox |

Bioterrorism Growing concern about bioterrorism (the use of biologic agents against civilian populations) has prompted the United States government to develop a comprehensive, coordinated defense strategy. Primary care clinicians will be crucial to the recognition of bioterrorism, since―in contrast to terrorism with chemical or physical agents―affected persons will usually be widely dispersed before disease manifestations appear. Potential agents of bioterrorism have been grouped into 3 categories, as follows:

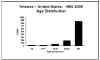

Bioterrorism should be suspected whenever clinicians encounter (1) a large number of cases of severe illnesses in previously-healthy persons; or (2) a single case of a rare infectious disease. Diseases of special importance include smallpox, anthrax, and pneumonic plague. Smallpox is diagnosed on the basis of the characteristic painful, pustular rash. The individual pustules of smallpox resemble those of chickenpox, but the rash of smallpox differs from that of chickenpox in 2 crucial ways. First, the pustules appear simultaneously (unlike in chickenpox, where the pustules appear in waves or crops). Second, the pustules are concentrated most heavily on the face and in the pharynx (unlike in chickenpox, where they usually start on the chest and back. The virus can be identified by electron microscopy, but no readily-available diagnostic procedures are available. Inhalational anthrax develops after the deposition of aerosolized spores of Bacillus anthracis into the lungs, where they are taken up by alveolar macrophages and transported to mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes. The illness is biphasic, as follows:

Pneumonic plague (discussed above) presents as fulminant bronchopneumonia. Blood and sputum cultures reveal gram-negative bacilli.

|

|||||

|

||||||